Last spring, Clark Library’s Covert Gallery featured an exhibit of archival research conducted by students in collaboration with the nonprofit organization Don’t Shoot PDX. Titled the “Liberated Archives,” the exhibit focused on UP’s history with racial injustice and resistance, as well as the broader Portland community.

This year’s Liberated Archives exhibit is located on the second floor of Shiley-Marcos Center for Design and Innovation and will be available for viewing until March 17. Spearheaded by social work instructor Anita Gooding and Vice President of Black Student Union (BSU) Olivia Outley, the exhibit features the collaboration with Don’t Shoot PDX as well as two new projects made in collaboration with BSU titled “Black Lines, Bold Stories” and “Letters in Black Ink.”

As Vice President of BSU, Outley said she felt a need to include current student voices and provide a platform for Black students to openly share their experiences at a predominately white institution.

“I was like, ‘We need to incorporate current Black voices on this campus, because there still is a need for a lot of change,’” Outley said. “And [UP] is big on talking about belonging, but a lot of people don't feel [like they belong], and what better way than to showcase their voices when talking about Black life at UP.”

“Black Lines, Bold Stories” is a collection of anonymous letters written by a BSU member of each class year. These letters feature personal narratives about the students’ experiences at UP.

The letters address topics such as the university’s work towards diversity, the lack of professors of color and finding a place of belonging at BSU.

“You can see the differences and the similarities throughout the different years that they've been here at UP,” Outley said. “And the stories are beautiful and they're impactful, and there's so much to be broken down in them.”

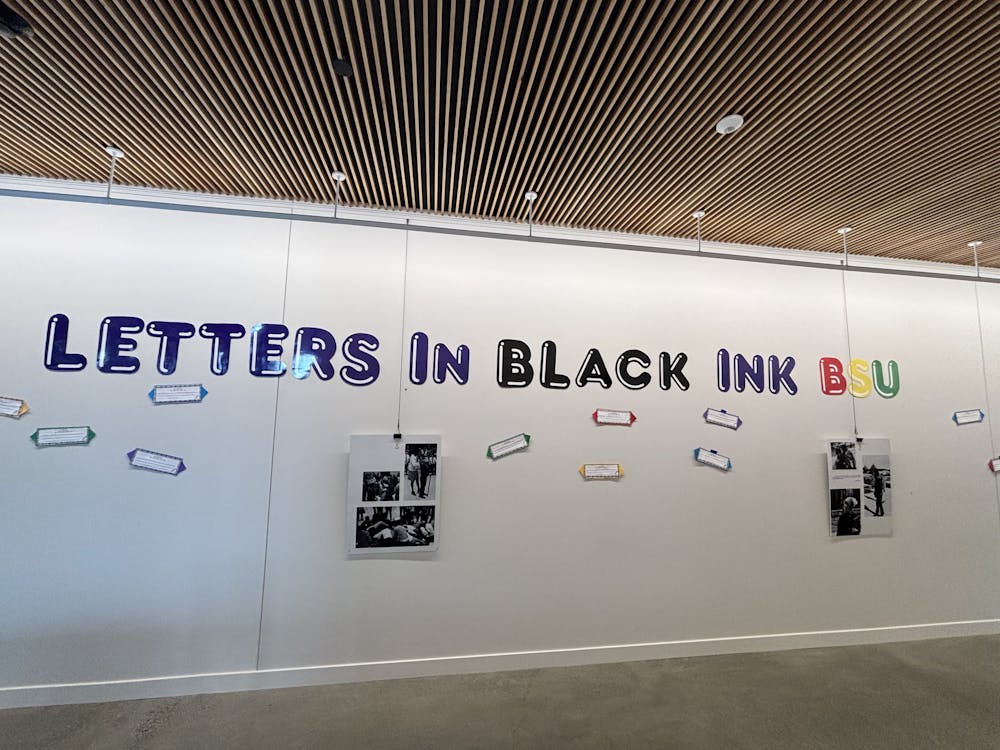

“Letters in Black Ink” features a wide collection of personal statements from BSU members, focusing on the aspect of belonging at UP. These written statements are also anonymous and were written by several BSU members during a general club meeting.

For Outley, having these statements and the letters offers a wider portrayal of the various experiences of Black students at UP. Some students wrote about feeling like they were included in the campus community, while others wrote about the feeling of isolation that comes with the lack of Black students on campus.

While it took hard work to bring this project to life, Outley found the motivation to continue with the project in community.

“Reading these statements just reaffirmed the work that I'm doing at UP for the Black community on campus and that my work, my time and my energy is worth something,” Outley said. “It is impacting people and making people feel welcomed and that I'm not the only one with these feelings of [not belonging] or code switching.”

Code switching refers to the modifications people make in speech, behavior or physical appearance to gain general acceptance from others. Historically, Black people have found it necessary to code switch in professional settings like work and school to avoid racial discrimination.

Outley hopes that the UP community views this exhibit as an opportunity to learn how to be more welcoming while reflecting on their own internal biases.

“If you're a professor, what can you do in the classroom to make the student feel more welcome?” Outley said. “If you're a friend, what can you do as a friend to make your peers feel that they can be themselves? If you’re a staff member on campus, what can you do to make that person just feel a little bit more welcome, a little more heard?”

Tiffany Marquez Escobar is the Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Editor for The Beacon. She can be reached at marqueze25@up.edu.