The average college student knows how hard it is to budget. With limited revenue coming into our wallets, we have to face difficult decisions on what to spend our money on. Things like skipping DoorDash for food at home or staying in when all your friends want to go out are just some ways students try to save some cash.

But what if your income suddenly dropped? You now have to see how you can make more money and conserve the money you already have while still meeting your needs.

The University faces a similar situation.

Still trying to recover from last year’s “freshman melt,” the University now faces a projected $17 million loss because of smaller-than-expected first-year enrollment, lower retention and having to offer higher financial aid packages.

“We're in a similar position to a lot of universities of our type,” Vice President for Finance & Operations Eric Barger said. “Community colleges are in worse shape right now than the small private and non-flagship, public universities. We're sort of in that middle group and performing in a similar way; we're all experiencing the same thing right now.”

So like the financially-challenged student, UP has to make some tough choices: how to bring in more money and how to spend less.

Why is UP in a deficit?

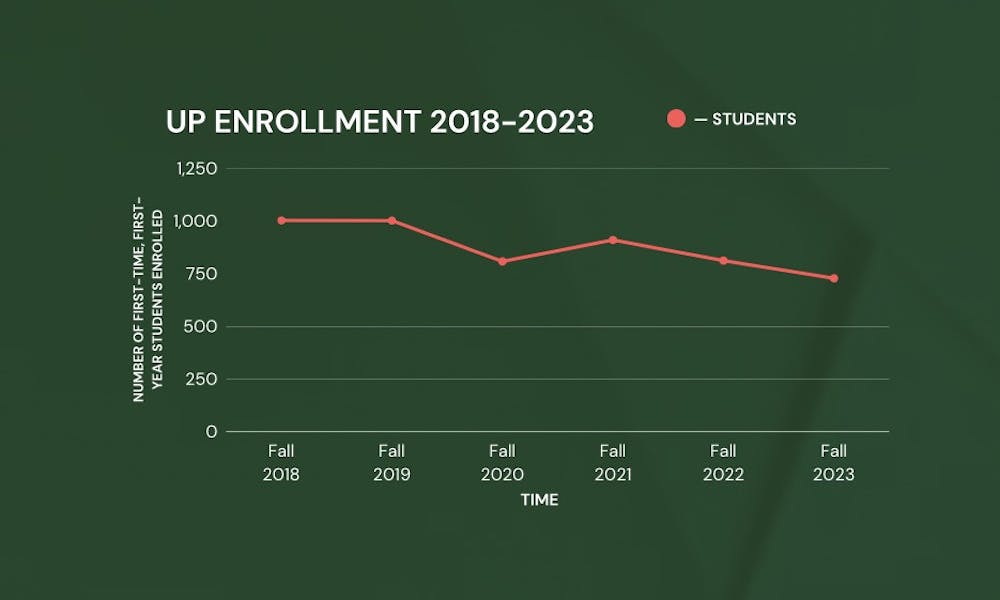

About 79% of UP’s budget comes from student tuition, room and board and meal plans. When the University loses students, it takes a big hit financially. Originally budgeting for a class size of 775 first-year students, actual results show 729 first-year students — a shortfall of 46 students.

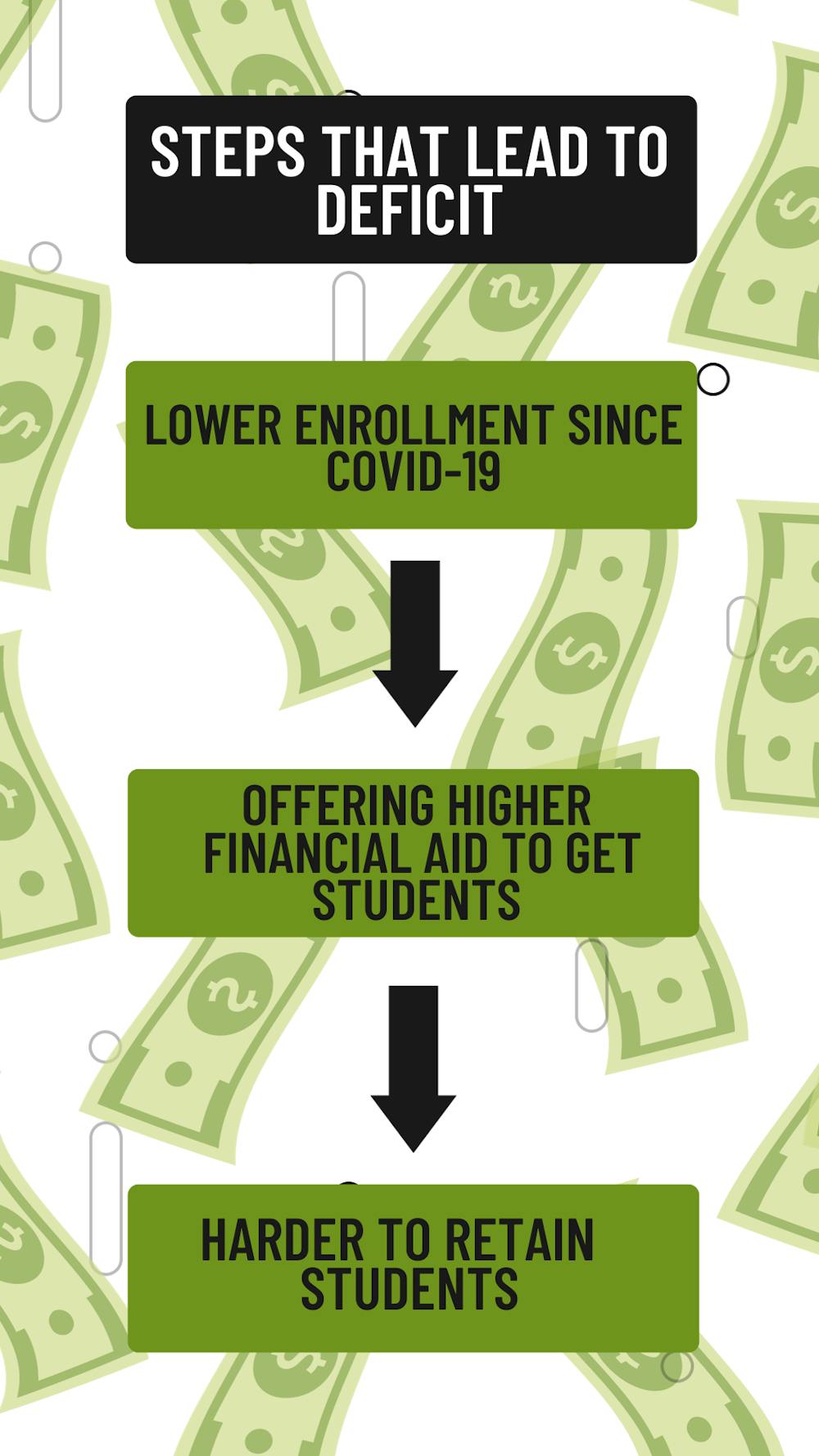

But it’s not just lower enrollment that’s causing UP’s deficit. It’s the combination of lower retention and higher financial aid packages, too.

In fact, Barger says that higher financial aid packages are a key factor.

“We've issued substantially more financial aid than in the past — an increase of like 10%,” Barger said. “It depends on how you look at it. If you look at the financial aid as a percentage of revenue, it's been an increase of about 8% over the last five years. If you look at it as growth of financial aid, it's like a 20% increase. So [it’s] to our students' benefit, clearly, because we're basically not charging any more than we did five years ago on a net basis.”

Declining enrollment across the country at colleges and universities after COVID-19 means that UP is now competing with other similar schools more fiercely than ever for the same pool of students.

Offering competitive financial aid packages is one way UP is trying to keep up.

One measure of that is the discount rate, which is the amount a university subsidizes tuition for students, on average. This year, UP’s discount rate was 54.6%, up from 52.2% last year. It means that this year the University is covering, on average 45.4% of the published tuition and fees, making it that much cheaper for students. To compare, the discount rate pre-pandemic in 2019 was 45.4%.

While these numbers are still projections, the discount rate translates to roughly $17 million more in financial aid than what UP would usually give to keep with the pace of increased tuition.

So while students have benefited from this change, it has largely reduced the amount of money available to the University.

“If we had the same discount rate, that's the institutional discount, we wouldn't have a deficit right now,” Barger said. “While we had a positive margin before, students have eaten up the positive margin that we had with the financial aid increase. The increase in financial aid for those fewer numbers [of] students have actually pushed us into a deficit.”

How could UP cut costs?

Without that positive revenue stream coming from tuition and other student expenses, UP has to find a way to make them. However, that is difficult with almost half of the school year almost over.

Barger says that the University is looking into short-term and long-term ways to cut costs to get back into that positive margin.

“It's gonna be a long road back to improving revenues,” Barger said. “In the short term, we'll probably have to look at more cost saving [methods] and anticipating running a deficit. We have the ability to run somewhat of a deficit for a short number of years and so we'll continue to do that probably for a few years.”

To cut costs, the University may consider further cutting retirement benefits, changing employee benefits and reducing other institutional expenses.

“I think that the key thing for us, though, as we're looking at these short term solutions, is we're trying to be very judicious in them,” Barger said. “We have a great team of people at the University of Portland and we want to keep those people here at the University. The people that work here mean a lot to me. So we're trying to be very judicious in how we reduce expenses and manage this deficit so that we can keep the people here for the long term.”Right now layoffs are not on the table, according to Barger, but he says it's not an “impossibility.” Cutting programs or classes are also not being considered at the moment.

“The provost is working with the Academic Senate to look at our academic programs to make sure that we've got the right portfolio of programs and that they're operating in an efficient way with the right sizes of faculty,” Barger said. “It's possible that we could, in the future, see fewer programs or we could see new programs added. But that's really a long term prospect.”

Barger also said that UP isn’t necessarily considering reducing financial aid. This is because UP has little debt and is still relatively strong financially compared to schools who have been discounting their tuition and fees for several years.

“We may try some different techniques,” Barger said. “We may find some other ways to manage that discount rate and offer scholarships in a different way going forward. But that'll be for new students coming in and the next few years. Right now, a lot of what we do is really driven and determined by the market.”

How could UP bring in more revenue?

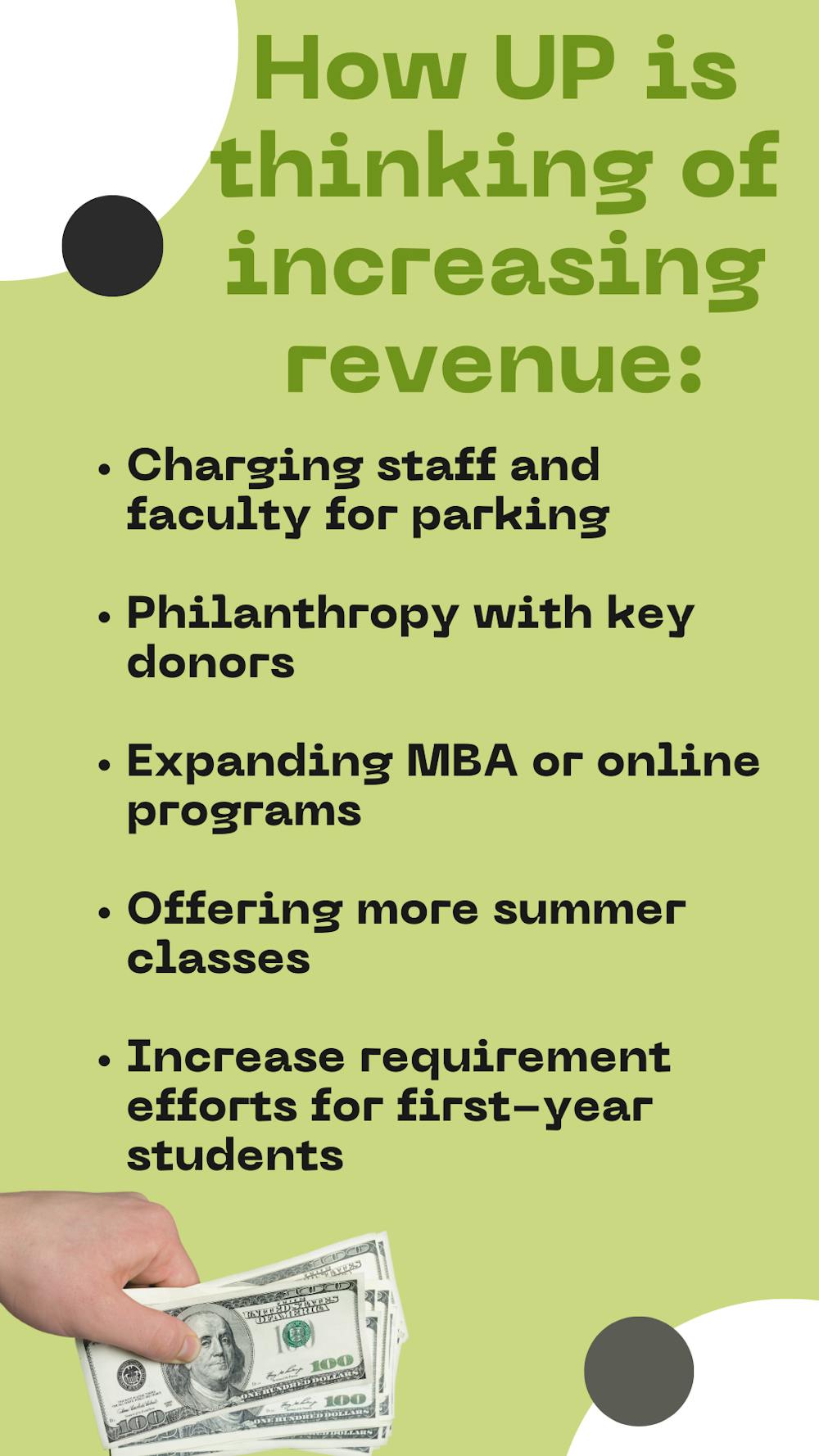

Charging staff and faculty for parking and philanthropy with key donors are the two ways UP is considering making revenue while they seek more long-term solutions. At a tuition-driven university, more students is really what they need to get them out of a deficit, according to Barger.

“It’s very difficult to make significant changes to our revenue this year because you recruit students,” Barger said. “We are mainly an undergraduate University, and so you really recruit students from their sophomore year in high school. So it's gonna be a long road back to improving revenues.”

Recruiting first-year students, however, is just as important as seeking to expand their current study body as well.

“We can explore to grow our student body as well, including online programs, particularly in the MBA world — maybe with summer programming and that sort of thing,” Barger said. “So there's a lot more that we can do with our facilities during the summer to help gain revenues as well. I think these are all realistic paths to growth as we go forward.”

Nothing is set in stone yet, according to Barger, who sent a survey to staff and faculty asking for their ideas.

“We're just trying to be creative,” Barger said. “We don't have a specific agenda or plan in mind right now. We're working on the background, kicking around ideas, some of which are good ideas, maybe some bad ideas.”

With the hiring of the new Vice President for Enrollment Management Mai Nhia Xiong-Chan, recruitment remains a key priority for the University — a goal outlined in UP’s Strategic Plan that gave momentum to changes in UP’s enrollment and retention tactics last spring.

“Our goal is actually to move back into this space of being a 4,000 student University,” Barger said. “Our infrastructure is really set up to be a school of that size. I don't think it's at all an unreasonable or an unachievable goal to move back into that space and even to grow after that.”

While experts predict the closure of small, private universities may continue until 2024 due to low enrollment, Barger reassures that UP will remain open.

“I expect that we will see more University closures and I don't expect University of Portland to be one of those,” Barger said.

Good news — UP has pretty solid footing.

Aside from having very little debt, UP has another marker that points to a possibly successful financial future: bond ratings. The Standard and Poor’s (S&P) bond rating gives an investment grade from AAA to D that reflects to investors an institution’s creditworthiness.

UP was given an “A” rating by S&P, which is on the higher end of the grade scale.

“So what they [S&P] said is that we believe in the University of Portland, we believe in its management team, we believe in UP’s history, we believe in its mission and we think you'll be successful,” Barger said. “Therefore, we have confidence in telling bondholders that [UP] is still a good investment.”

Barger believes that this a strong indication that UP will eventually recover from the deficit, though it is unclear how long that will take.

“I think that with that [S&P] outside confirmation, telling us what we already know about ourselves — that we're a strong, resilient university with resources, a great Board of Regents, a great management team, a great group of faculty and staff that makes this thing happen,” Barger said. “I believe that we will be able to reverse course, it'll take a number of years though.”

What’s next?

UP leadership is currently working on a plan to address UP’s financial future for the Board of Regents. Using staff and faculty feedback, they are ultimately trying to make a plan that's best for the University in the long run.

“This is a plan to create financial sustainability,” Barger said in an email. “The short-term elements of the plan will be to lessen or mitigate (not eliminate) the University’s projected current year losses. The long-term elements of the plan will be about strategic investment and growth.”

The plan will be presented to the Board of Regents in January, though it’s unknown at this time what information will be made public, if any at all.

Whatever the University decides to do going forward, Barger says the goal is to preserve the student experience.

“At our tuition-driven university, students remain our first priority,” Barger said. “Our hope is that whatever changes we make, we won't impact the student experience at all. That's what we're working to achieve. That's the message I would have for students.”

Kimberly Cortez is the Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Editor for The Beacon. They can be reached at cortez25@up.edu.