What do a mechanical engineer and a ballerina have in common? Upon first glance, little to nothing. But the STEM field is now using quantifiable metrics and coding to further study the world of dance.

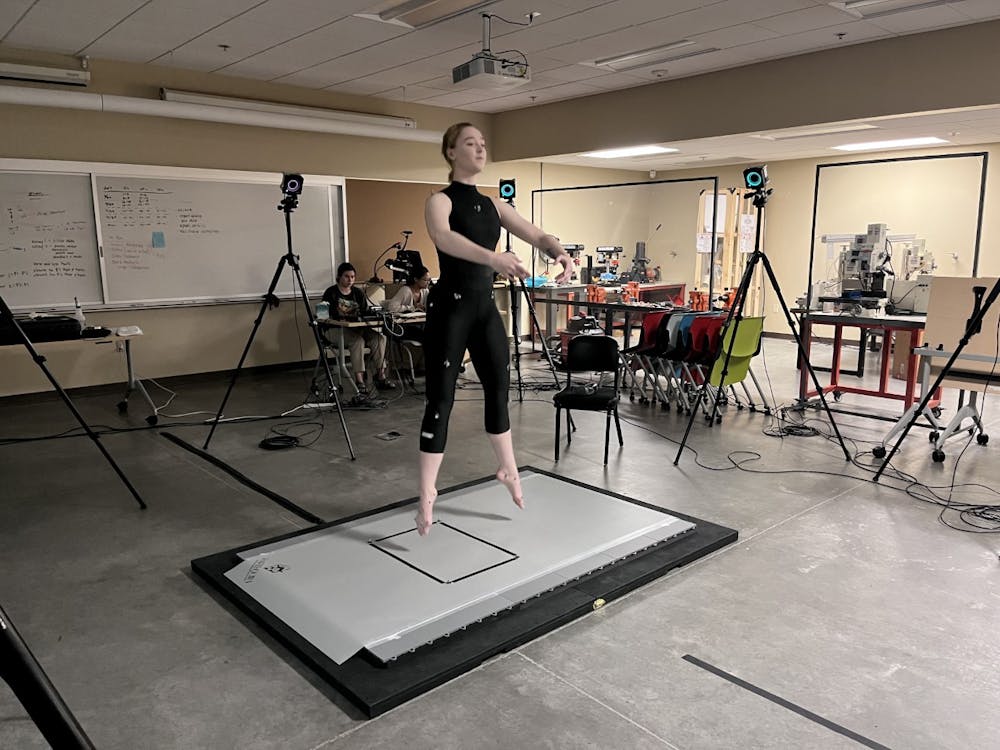

Trading in tutus for reflective markers, an audience for cameras and a stage for a force plate, a group of three ballerinas took to the floor of Shiley Hall this summer.

The complete research team included biology professor Glenna Clifton, biomechanics professor Kathleen Bieryla and undergraduate researchers, junior Katt Gamblin and senior Jessica Yoshioka.

Ever since reading Kenneth Laws’s “Physics and the Art of Dance” in high school, Clifton has been interested in researching the intersection of where science meets art. Now with a background in both comparative biomechanics and dance, Clifton leapt into the project this summer.

“I've been really interested in understanding dance both from a visceral level in terms of knowing the movement and from a scientific level,” Clifton said.

Research combining biomechanics and dance gave researchers some flexibility and room for innovation. Because this is a newer area of research, the UP team was able to explore this topic before bigger and faster institutions got ahold of it, according to Bieryla.

One main research question the team wanted to answer was whether a difference between styles increases the possibility of injury.

“It seemed very unique in its own way because in disciplines like physics, you are often trying to solve a problem,” Yoshioka said. “This was different, we wanted to see how dancers jumped and then figure out what was wrong. I think it was cool because we were looking for the problem.”

Two styles of jumps were chosen to be studied: Balanchine and classical.

The Balanchine style was created by Russian dance master George Balanchine. This style features high leg extensions, exaggerated arm movements and extreme turnout. The classical style on the other hand — or foot — focuses on straight lines and precision.

“One of the things that he [Balanchine] pushed to the extremes is really fast footwork, and associated with that is jumping without putting your heels down,” Clifton said. “So that’s a common correction that you hear in ballet classes. It’s put your heels down or don’t put your heels down based off of what the teacher is trained in.”

While the evolution of dance is far from predictable, the effects of force from the type of jump are much more measurable.

Pre-dance isn’t the only time for stretching. During physical activity connective tissues in the muscles stretch and retract, similar to a rubber band. The different connective effects between styles was a point of interest for the research team.

Before the theories were put to the test, it was predicted that the balanchine jumps would increase the risk of stress fractures or other injury. Prior to reaching out to dancers, researchers customized the force plate and coded the program for analyzing the jumps.

In lieu of a typical backstage area, Gamblin and Yoshioka applied reflective strips to dancers in order to track movement. Cameras were then set up around the force plate and data collection began, courtesy of the Optitrack motion capture system.

There is a lot to be gained from a scientific understanding of these two styles of dance.

“Before we can get to things like footwear design or cross training, or strengthen ways of mitigating some of the injuries that may occur, we first have to even understand what's happening,” Clifton said. “So we're at that first stage of trying to understand if there are actual differences between the two ways of dancing these jumps.”

Because the force plate was designed to be easy to break apart and reconstruct, this study is mobile. Next summer, you can expect to see this study on the road with the goal of reaching out to professional training programs in the area.

Regional summer dance intensives bring forth a level of precision and rigor that contribute to heightened accuracy in biometric studies. This increased sample size will hopefully allow differences between jump styles to be identified.

With the curtains closing on summer research, both undergraduates walked away with valuable research experience. Gamblin attended a biomedical engineering society conference in San Antonio, Texas to share their research proposal with professionals in the field. Yoshioka hopes to apply what they’ve learned from this research to their intended career goals.

“I've have always had an interest in footwear,” Yoshioka said. “This research helped me to gain experience in a related field and grow, especially in biomechanics. In my future career, I really want to combine STEM and dance in some way.”

If your interests span more unconventional topics, do not be deterred from participating in undergraduate research. The research field has never been more interdisciplinary and there is truly something out there for everyone.

“I think it's a really nice intersection,” Bieryla said. “It can get a lot of students interested who may have not thought about oh, biomechanics is the thing I can do or interested in. So it's a different area. I think a lot of times it sounds more scary. And finding topics that students would want to get interested in and be a part of, I think is good.”

Ellie Black is a reporter for The Beacon. She can be reached at blacke24@up.edu.