From braving the cold in Greenland to analyzing religious rhetoric, UP students were involved in a variety of research projects this summer. If you think research in your discipline does not exist, this may convince you otherwise. Here’s a brief look into five UP students’ summer research.

Impacts of rhetoric on the Catholic Church’s response to the sex abuse crisis

You may have heard of the UP Collaborative Humanities Investigating Religion and Power (CHIRP) LAB gaining momentum around campus, but only have a vague sense of what this Lab is all about.

Sophia Osuna ‘24 spent the summer doing research for the CHIRP Lab on the Catholic Church’s response to the sex abuse crisis with professor of theology David Turnbloom. Along with Noah Lamberger ‘22, Kate Seddon ‘24, and Meg Breen ‘23, Osuna brought an important outside perspective as the only communications major.

“I focused on rhetoric and language and how we make meaning out of the words we use,” Osuna said.

The group’s research focus was analyzing the language used in documents/press releases of the Catholic Church’s response to see how it influenced the public. They found many of the rhetorical devices/strategies used by the Church mimicked manipulative devices in domestic abuse and intimate partner crises.

“This research is important because power dynamics are everywhere and we’re all being influenced by it,” Osuna said. “If you haven’t experienced it yourself, chances are someone you know has.”

Through their research, they began to ask questions. How does the language the Church use still facilitate abuse beyond the acts of sex abuse itself? How does that shape a community? What are better ways to respond to a crisis like that?

To find answers to these questions they researched trauma informed care and met with local sexual assault resource centers to understand how language is used in those places. Meanwhile, Osuna was busy growing the CHIRP Lab Instagram and conducting outreach to hire more students.

“There's so much apprehension around the words ‘research’ and ‘theology’ because there's so many expectations of what you think the experience will be,” Osuna said. “For me, I had no idea that I would be walking into a room of individuals who are so excited to show up every single day and so excited to talk and learn and grow together.”

In addition to working with passionate students, Osuna was particularly grateful to work with Turnbloom.

“His mentorship was such an important part of my research, not just academically, but personally as well,” Osuna said.

Pervious pavement: the ties between environmental engineering and water health

Jackson Kaye ‘24, became a runoff expert during the spring semester by collecting stormwater and conducting background research in preparation for summer research. Working with engineering professor Cara Poor, Kaye investigated the filtration ability of pervious concrete and porous asphalt, seeking creative ways to prevent nonpoint source pollution from reaching water pipes and bodies of water.

With 36.7 inches of rain a year, Portland is notorious for its precipitation. And where rain goes, runoff follows. Stormwater flowing over streets in urban areas accumulates heavy metals and chemicals, pulling toxic material into nearby waterways. In turn, affecting ecological processes and human health. Permeable concrete could further the problem, but may also provide a potential solution.

“We would run different analyses on water samples, all of the different things that the city of Portland might want to see,” Kaye said.

A concern with permeable streets is that polluted stormwater could reach and spread contaminants in water pipes below. But permeable pavement could also work as a filter for fallen water, removing pollutants and mitigating the damaging effects of urban runoff. These were the questions being asked during this project's conception.

“I chose this specifically because I’m inspired by environmentalism and this is the best way to make myself stand out,” Kaye said. “And writing a paper, that is such a unique opportunity that you wouldn’t get unless you went to graduate school.”

Two other students, Maya Struzak ‘24 and Abby Radke ‘23, were also researching stormwater filtration, with a focus on soil layering instead. They were working with engineering professor Jordy Wolfand.

Stormwater gathered in the spring was run through samples of each type of pavement. This was followed by testing for copper, zinc, total nitrogen, ammonia, nitrate, total phosphorus, phosphate and pH. Filtration results have yet to be analyzed, with research most likely wrapping up this fall, steadily moving towards the end goal of publishing a peer-reviewed research paper.

“I feel like my skills improved tremendously through this experience,” Kaye said. “ I’m using it to pursue a future goal.”

It can be a hard task to find and land a summer internship on your own, with hiring platforms such as Handshake or Indeed containing an overload of information. Kaye began his search within UP, at the Shiley Pulse.Applying for research positions can be intimidating but Kaye was grateful he took the leap of faith. He encourages other undergraduate students to do the same.

“Keep applying,” Kaye said. “I applied twice and didn’t get it. When I applied a third time, it showed my passion for it. So that’s huge. Keep pushing.”

Kaye is a civil engineering student with an environmental engineering minor who aspires to work with water management or green infrastructure in the future. He applied to undergraduate research to further his professional skill set and is passionate about wanting to gain experience in environmental engineering.

“I think that research is a great opportunity,” Kaye said. “It shows that you’re willing to go above and beyond, and that you have a good worth ethic and are able to do research and school.”

Buried lakes, professional explosives and a summer on not so thin ice

Ice sheets are integral to regulating global temperature by reflecting solar radiation. Kristina Rodney ‘23 traversed the melted landscape of Greenland’s glaciers with environmental studies professor Kiya Riverman, seeking answers about the first studied subglacial lake in one of the most uninhabitable places on Earth.

Glacial ice is extremely dynamic, going through patterns of accumulation and ablation. Periods of accumulation are dictated by an increase of precipitation and ice sheet build up. This is interrupted by periods of ablation or melting.

Preparation for the trip began by analyzing radar data from 2018 to pinpoint exactly where the lake was in northwest Greenland.

“It’s really weird that there’s a lake in an accumulation zone, that’s where our lake is. There is no melt happening, so why is there water happening?” Rodney questioned.

Landing in Tuli, Greenland, Rodney and Riverman spent a few days going over how to use their radar equipment, practicing for the actual site. The next three weeks were spent in a camp above the subglacial lake. They used explosives to create sound waves in order to try and determine where inflows of water were located, seeking possible explanations for the existence of the lake. Other research teams on this project used radar and seismic regiments to study this hidden body of water.

With her fingers still numb from long term exposure to cold, acting as tribute to her summer spent under the Greenland sun, Rodney is looking forward to future work in the field of ice and snow.

“I definitely want to do a master’s program in glacial hydrology, which will most likely fall under geology,” Rodney said. “I am interested in mountain glaciers and how they change and the hydrology they give to local communities. That intersection between science and humanity, walking that line is really fun.”

Microplastics in moss, a possible bioindicator for pollution

We are perpetually shedding microplastics. There are infinite anthropogenic sources, from the cars we drive to the clothes we wear. A possible solution to identifying and remediating microplastic hotspots may be found by turning to an organism often overlooked, moss.

Involved with a moss digestion lab at Portland State University (PSU), Nathan Rhodes ‘24, spent several days in the field collecting moss from around the Portland metro area. They worked to answer questions posed by graduate students and professors at PSU, UP and Utah State.

“Can we use moss as a bioindicator for microplastic pollution?” Rhodes said. “We wanted to see if we could use moss as an analogue for where microplastics are in the air in order to track them. The second objective was to see where there are hotspots of microplastics in urban areas, and how this information can be used to help inform policies on plastic recycling.”

Moss collection was followed up by lab work, which consisted of breaking down the moss to isolate the microplastics it contained, counting the types and quantities of microplastics, and data entry.

“About 10% was field work, which was kind of backwards from the description of the position,” Rhodes said. “It was originally described as 70% field work and 30% office work. That was kind of disappointing to have that as a reality. I guess that’s just part of research sometimes, the unexpected things that happen.”

There were several issues that arose from such a large project, one being funding. While Rhodes was paid through UP, graduate students at PSU were not paid all summer long, even though they were promised a stipend for their long hours spent in the lab.

“People were stonewalled by the university,” Rhodes said. “They were like, “you’re going to be paid, you’re going to be paid, you’re going to be paid, and then they never were.”

One graduate student left the project two weeks in, another nine weeks, in search of a job that paid them for their time.

“I feel like this experience definitely pushed me away from wanting to do research. but in a way it also made me want to pursue it as a career or in grad school, to show other people that it doesn’t have to be like that. I am still very passionate about studying environmental science,” said Rhodes.

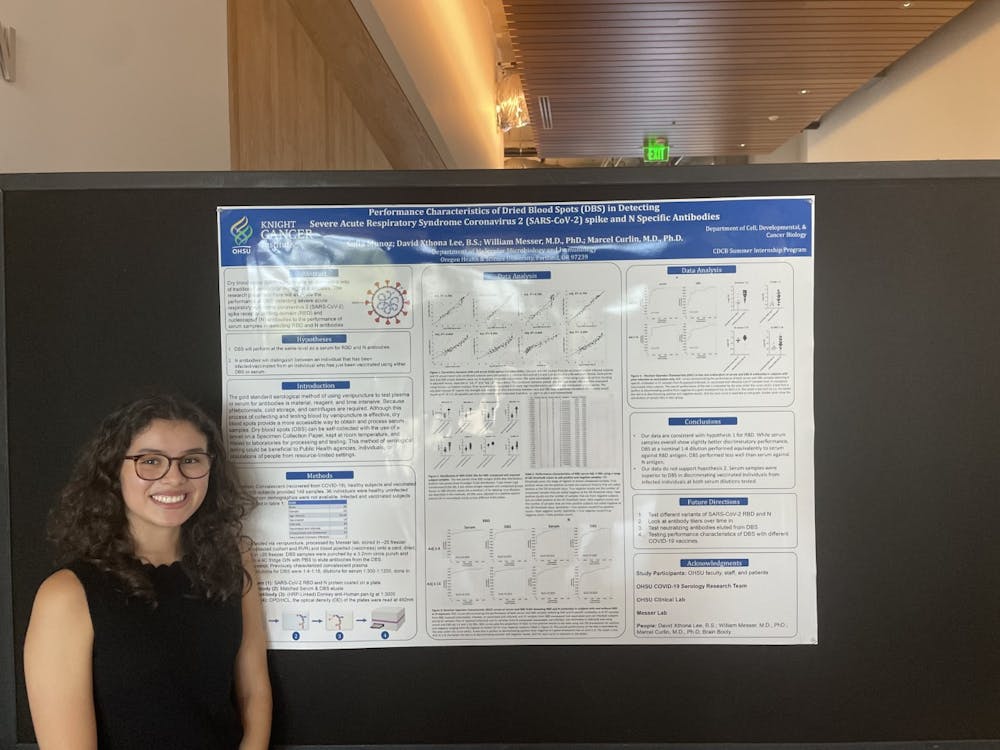

COVID-19 research at OHSU, testing the effectiveness of dried blood spots

Sofia Muñoz ‘25 shows that summer research through UP is not the only option. Scouring the web for more opportunities, Muñoz found an internship conducting COVID-19 cell biology research at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU).

“For me, I wanted to do summer research [because] I didn’t want to lose knowledge over the summer,” Muñoz said. “I wanted to learn during those months. I found that the research was intense, but intense in a good way. I actually felt like an adult doing the work.”

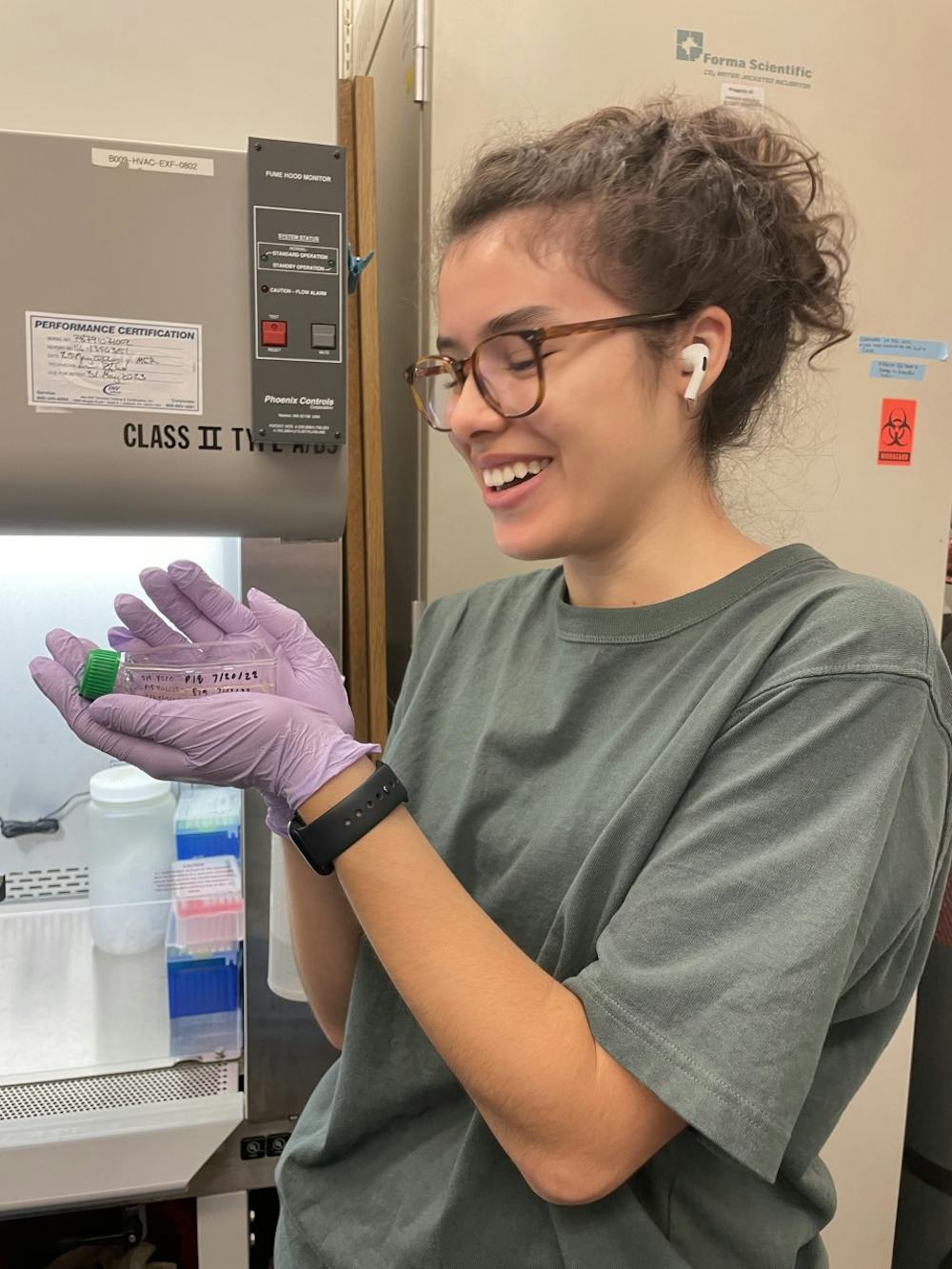

In a Flavivirus lab, you can find Muñoz in her element experimenting with the Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for an ongoing COVID-19 project. Their goal was to determine whether a dried blood spot is as effective as a normal serum in detecting antibodies for COVID-19.

Muñoz with research sample in the OHSU lab. Photo courtesy of Sofia Muñoz

Dried blood spots are more favorable in comparison to serums as they can be kept at room temperature and the dried blood spot cards can be mailed to allow for self-testing.

“This research is important to the field of public health as dried blood spot tests could be useful for people who don’t have the resources to go to a hospital or phlebotomist to get their blood drawn,” Muñoz said.

Although she loved hands-on research and doing cell culture in her free time, Muñoz’s favorite part of the internship was actually the community and connections it brought her.

“What I was really excited about was getting to do work with PhD students and research assistants, as well as going to weekly lectures and journal clubs to learn about new research projects,” Muñoz said.

Although Muñoz was quite certain of her desire to attend medical school in the future, this research made her realize that she loves being in a lab, opening up the possibility of doing PhD lab research instead. Either way, Muñoz knows she wants to continue trying other types of research next summer.

Sophia Truempi is a reporter for The Beacon. She can be reached at truempi22@up.edu.

Ellie Black is a reporter for The Beacon. She can be reached at blacke24@up.edu.