Oregon isn’t usually the state that pops in your mind when you think of earthquakes. Your brain usually takes you somewhere like California, or maybe Alaska and Hawaii. But the Beaver State has a history of earthquakes dating back to at least the 1700s. Oregon experiences fairly frequent earthquakes, in fact, but they often go unfelt because of their low magnitude, typically no more than 1.5-2.5 magnitude.

These tiny earthquakes occur on small local fault lines. Faults, according to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), are fractures in two large blocks of rock. Earthquakes occur when these blocks of rock move — or slip — relative to each other, releasing energy into the surrounding rock in the form of seismic waves. These waves are what damage landscapes and man-made structures.

You might be asking yourself, what does this mean for the University of Portland?

“There's a few different ways that land can deform during earthquakes,” environmental science professor Kristen Sweeney said. “Landslides are definitely one of them. Those are typically going to occur in locations that have steep slopes. So in the Portland metro area that would be expected in the West Hills, for example. And then Forest Park and also along the Bluff and as well as Mount Tabor.”

In the event of an earthquake strong enough to trigger landslides, the University of Portland isn’t likely to see much land deformation.

“On the Bluff, aside from the bit that's right along the edge that is likely to have some landsliding,” Sweeney said. “The soils that underlie the Bluff are Missoula flood deposits from the Missoula floods. They're very well drained, which means if you dig a hole on campus — unless you hit the irrigation system — you don't find water basically, so it drains pretty well.”

The academic buildings and dorms are built to the city of Portland’s modern seismic codes. Older buildings receive seismic retrofits to reflect a better understanding of how earthquakes damage structures. Mehling Hall, built in 1964, received one such upgrade over the summer of 2021.

Faultline Offshoot from the Ridgecrest earthquakes in California in 2019.

Image by Ben Brooks, geophysicist with US Geological Survey

“It would have been built to the code at the time and obviously with higher rise buildings you want to try to provide better structural reinforcement over time,” Associate Vice President for Construction Facilities, David Hobbs said. “And so what this project aimed to do was to provide seismic strengthening throughout the building, from the basement all the way through the roof structure to help alleviate and bring it closer into alignment with better seismic structural stability.”

According to Hobbs, the retrofit cost approximately $5 million and is part of a multiyear project starting in the dorm’s basement, retrofitting two floors per year, as the university budget allows. Floors seven and eight of Mehling were retrofitted last summer, leaving only the eighth floor and the roof to be completed.

Another hazard associated with earthquakes is liquefaction. Liquefaction is when wet soil is shaken and acts more like liquid than a solid. The result is that anything on the ground, like buildings or cars, will sink, while underground infrastructure like manholes or sewer pipes will rise.

“This is a problem for places typically that are along river corridors or other perennially saturated areas like wetlands,” Sweeney said. “We worry about this for a lot of the industrial areas near Swan Island. A lot of downtown Portland is sort of in a floodplain, and then also places in East Portland that are along Johnson Creek.”

Most of the landslides in Forest Park or the Columbia River Gorge are caused by water infiltrating soil on hillsides, which causes them to become unstable and collapse downhill. Only the edges of the Bluff will experience landsliding during an earthquake; academic buildings and dorms — which are far from steep slopes — are likely safe from those specific hazards.

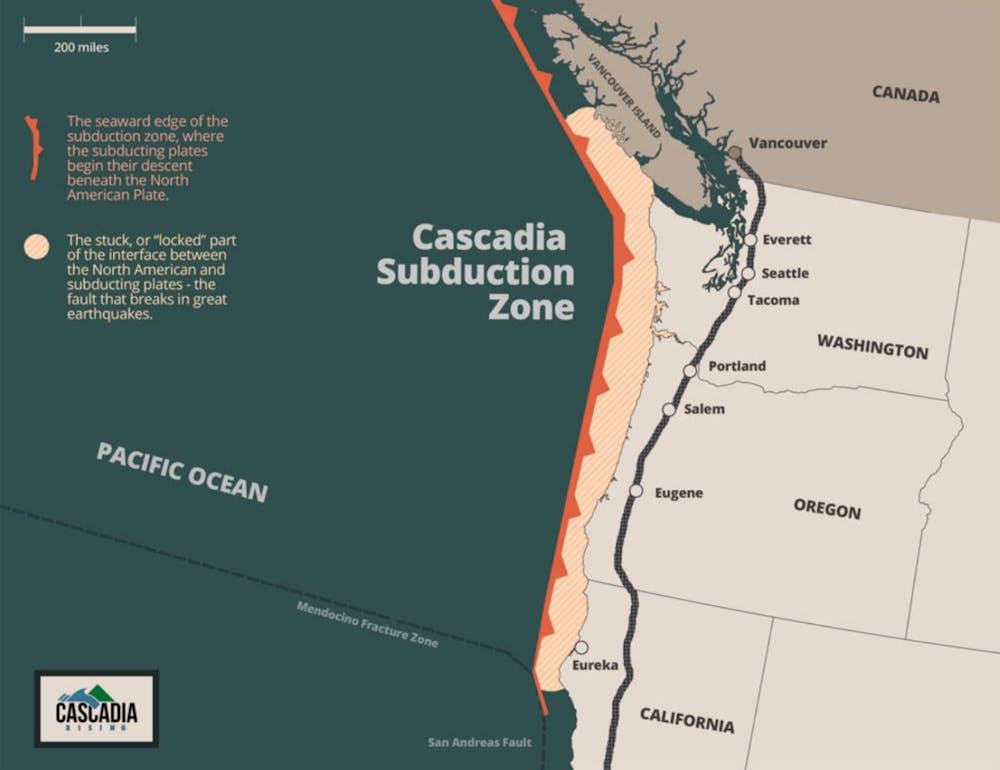

Oregon has seen larger earthquakes though. Off the cold, windswept coast, lies the Cascadia Subduction Zone, a 600-mile long fault line that stretches from Northern California to British Columbia. Earthquakes occur along the fault as the oceanic Juan de Fuca tectonic plate moves east, sliding under the North American plate.

The tension between the North American and Juan de Fuca plates has generated 41 quakes in the past 10,000 years, averaging out to one approximately every 250 years. Scientists estimate the magnitudes of these quakes range from 8.0 to 9.2, depending on how much of the fault ruptures.

The risk here is difficult to quantify. Earthquakes aren’t like hurricanes or tornadoes, there’s no metric or telltale sign that one will happen where you are at any given moment. Scientists know where they happen historically, and that helps with preparation. Knowing what to do before, during and after an earthquake can be more important than knowing when one is going to happen though.

Other universities like Lewis and Clark College, University of Oregon and Oregon State University have offices of emergency management, but the University of Portland does not. Often larger student populations and better funding make emergency management easier to access. These offices coordinate with city and county emergency operations centers to better prepare their institutions for crises.

At UP, the role of emergency management falls to Campus Safety, whose job, according to Director of Campus Safety Sara Westbrook, begins in the aftermath.

“We're just going to have to gather together the decision makers of this University,” Westbrook said. “And depending on how big [the earthquake] is, we would be collaborating with the city and county and whoever else is available to help and find out what resources we have and make decisions on how we're going to move forward in that moment.”

Seeing as most students rent the places they live in, be it dorms or houses, it can be difficult to take the kinds of precautions that home owners do, like bolting their homes to their foundations or creating a robust earthquake kit. Despite that, even knowing what you can do can be enough to save people’s lives in an earthquake. Plenty of universities have resources to help with this, UP included.

Here are some things you can do before, during and after an earthquake to stay safe:

Before an earthquake: identify evacuation routes out of buildings you frequent, move large objects to lower shelves so they can’t fall on you, and identify spaces where you can drop, cover and hold on. If you can, gather some supplies like flashlights, a radio, extra water and food and camping gear outside of your house in case you can’t go back into your house when the shaking stops.

During an earthquake: you should stop, cover and hold. If you can, take shelter under sturdy furniture and protect your head and neck. If there’s no furniture, drop into the fetal position and protect your head and neck. Avoid windows and unsecured objects. If you’re in a building, stay inside until the shaking stops. If you’re outdoors, stay away from buildings, trees, power lines and utility poles. If you’re in a car, pull over.

After an earthquake: exit the building you are in via your predetermined evacuation route and do not re-enter buildings until they have been declared safe by emergency authorities.

Will Mulligan is a reporter with the Beacon. He can be reached at mulligan22@up.edu.