An expert in Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) work in higher education spent three days on campus the week before Thanksgiving talking to students, faculty and staff about UP’s strengths and weaknesses in making the University more diverse and inclusive.

By the end of her meetings, she had 36 pages of notes.

UP hired Elizabeth Ortiz, vice president of the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education and vice president for Institutional Diversity and Equity at DePaul University, to assess the DEI climate at UP.

In light of the findings from the investigation sparked by former vice president for Human Resources Sandy Chung’s July 2020 op-ed, the Board of Regents called for a DEI assessment by an outside consultant. Associate Provost for International Education, Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Eduardo Contreras says that they hope the report will be released to the UP community by February.

Ortiz has done similar assessments at several other universities.

“I let administrators know that it is our job to listen and then to transform.” Ortiz said, “We need to say, ‘Okay, this is the issue. Now, how do we form action plans to resolve whatever the issue is?’ Our job is to be the problem-solvers.”

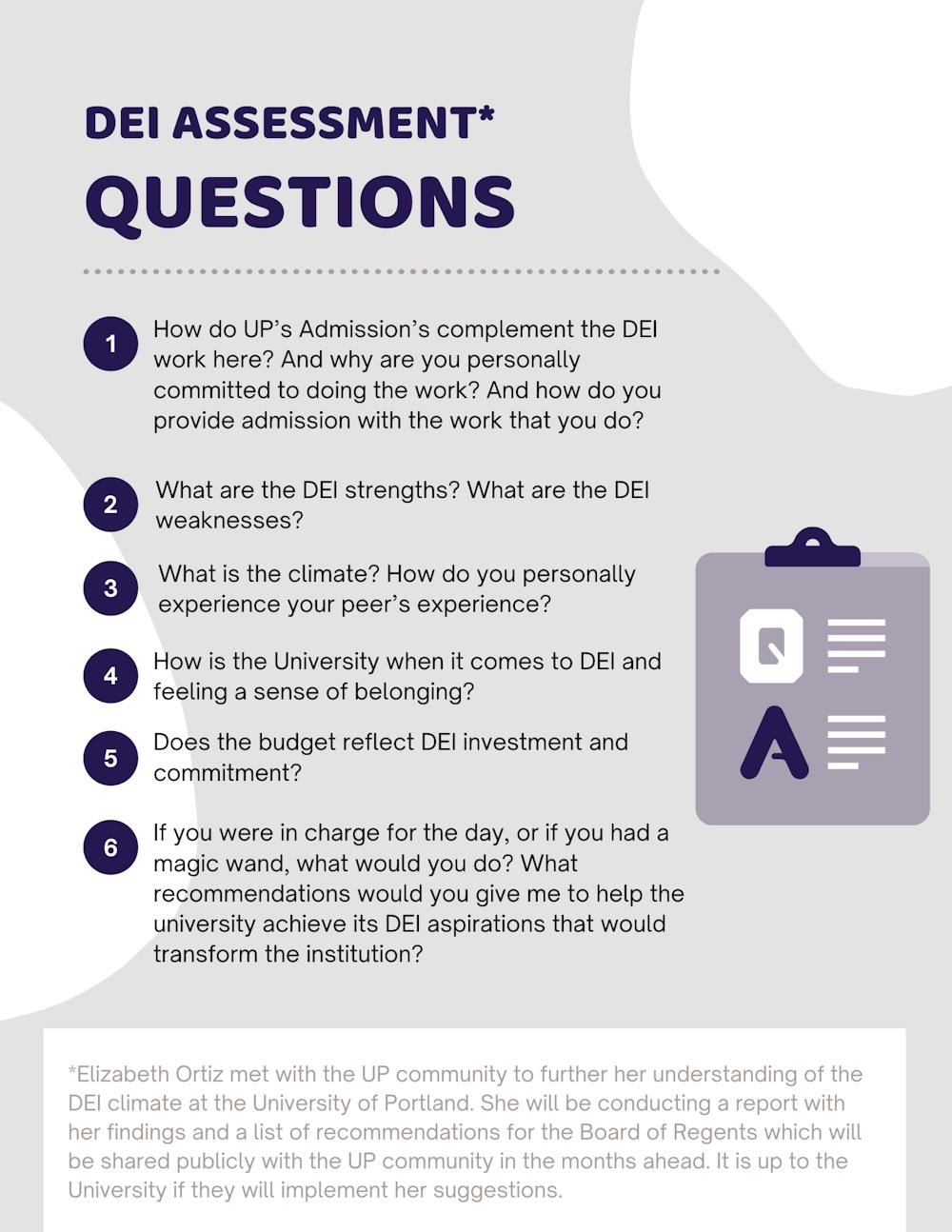

On Nov. 17-19, she met separately with select students, faculty, staff and members of the Holy Cross Community who were granted confidentiality. Ortiz posed six questions to participants, which she said sparked a rich dialogue.

Ortiz originally had 20 questions prepared to ask her interviewees but ended up only asking these 6 questions during her interviews. Canva by Brie Haro

“The individuals that I met with gave me a tremendous gift,” Ortiz said. “They trusted me, they told me how they felt, their narratives. That's a sacred trust.”

Ortiz found that one of UP’s strengths is its strong sense of community building. Students expressed their sense of unity to Ortiz while creating student groups and often feel that they can lean on each other for support.

However, Ortiz said some marginalized students said they felt isolated at UP, a problem magnified by the lack of diverse and inclusive faculty.

“They did mention some [instances] such as, ‘I never had an African-American professor until my fourth year here, and I'm a senior.’” Ortiz said, “They mentioned microaggressions in the classroom where they would have to get up and speak for their whole identity group and how they feel on ‘x’ issues.”

Students called for a more centralized DEI resource center to feel better supported by the University.

“They felt that they were, in many cases, experiencing microaggressions in the classroom,” Ortiz said. “That many times they felt they were doing the DEI work for the University. Even though they love forming these clubs, [students] shouldn't have to in lieu of their academic studies and preparing for exams. They really thought they were doing the heavy lifting of DEI work on campus.”

The Diversity Center came up when talking about what students need in order to feel supported and recognized by UP.

“They didn't feel that there were supportive spaces,” Ortiz said. “[Students] Also wanted a Diversity Resource Center. They felt that they really needed a place, a space, to be their full identity.”

Many of Ortiz’s initial findings are common themes at many institutions.

“I think there's always a challenge between students and administration,” Ortiz said, “Because there are misunderstandings between how you perceive the world and how I perceive the world. That's why I think active listening is so important, it’s how we really hear each other and make that discernment when students are saying, ‘This is what we need.’ They're not saying this as a critique, it's an honest cry for a need.”

Two students — senior Grace Adam and junior Grace Fortson, who are actively involved in DEI work at the university — talked to The Beacon about their frustrations and how they felt about seeing UP hire an outside consultant.

“Having an outside perspective really changes the dynamic of the recommendations,” Fortson said. “There's no response like, ‘We need to cover this up’ or ‘No, that's not actually happening because UP isn't racist.’. [Ortiz] isn’t trying to fight us, she’s just trying to be helpful and say ‘No, this is happening and we should address that.’”

Adam and Fortson agreed that students with marginalized identities feel unheard, isolated and bombarded with the DEI workload.

Adam said that she has tried to point out tokenism after being asked to give feedback on the Diversity Center and said she doesn’t have the time to contribute to every conversation or committee about DEI matters.

“I emailed her back and said you need to have more students involved.” Adam said, “Two students of color is not enough. I don't have the capacity to do this all the time. Some weeks I might, some weeks I might not. Just because what I think might be good doesn't necessarily mean what other students of color might think. I can't speak for everyone.”

While they are passionate about the work they do, they realized that they didn’t inherently ask to be a part of these task forces and committees, they were thrown into it.

Fortson said that getting into diversity work at the university, in general, is challenging because it lacks recognition as a problem at UP. Adam said that she didn’t recognize the problems until working on DEI issues with colleagues at UP two summers ago.

“So much of why DEI work at UP is so hard is because it is so decentralized,” Fortson said. “Because nobody is getting compensated for the work on top of your school, your work, any outside responsibility, so nobody has enough time to just dedicate to this. Which makes it very inconsistent and very difficult to actually build something.”

Adam and Fortson ask and encourage students to get more involved, especially if they want to support the student leaders who aren’t getting paid for the work they do and are having to relive their traumatic experiences when explaining where they’re coming from to the University.

“We're losing more [volunteers] than we're gaining from doing this work.” Adam said, “That's what it feels like at this very moment and that's tiring.”

Adam encouraged students who want to get informed to attend diversity clubs' events. She said that most of this information is shared and held in these clubs.

“Another really important thing for students to do is once this report comes out, to actually demand that the University do what Dr. Ortiz recommends.” Fortson said, “Because I think it's so easy when we are all in the system that is so undermining of our sense of agency, sanity and rationale, that we forget that we are the ones who have power here. The school doesn't exist without us.”

Fortson hopes to see actual structures be put in place so that students don't have to keep doing this work and for UP to take accountability for the lack of recognition of DEI issues that are going unchecked.

“That is what the department is supposed to be doing,” Forston said. “If we want to keep bringing students of color and other marginalized groups here to this university so that they [UP] can fill out some diversity quota, then they have to support them. Otherwise, it’s like hitting them over the head.”

Contreras selected Ortiz based on her many years in DEI work. He is excited about the change Ortiz’s assessment could bring to UP, even if the conversations were difficult.

“Even though a lot of that is hard to hear, it still gives me hope that we are hearing [these problems],” Contreras said, “and that we're having the conversation in a way that we haven't had in the six years that I've been here.”

Members of the UP community who participated in the interviews with Dr. Ortiz were chosen on a comprehensive basis, according to Contreras.

“The students interviewed were active in DEI committees on campus and student groups representing a wide range of interests and identities including those from historically marginalized groups,” Contreras said.

Ortiz had students from a wide range of backgrounds and positions on campus, including some who are part of the Associated Students of the University of Portland (ASUP), work study and other career identifying groups, as well as those who are interested in the topic.

Contreras also said that there was an array of faculty, members within the Board of Regents, the campus leadership core team, the President’s leadership cabinet, the Provost Council and members of the Holy Cross Community.

He says that, once the final report is finished, DEI at UP will shift into an ongoing conversation of how to ensure everyone has a feeling of respect and belonging.

“One of the things that I knew when we were given the opportunity by the Board (of Regents) to do a DEI assessment is that out of this conversation, there could be some hope.” Contreras said, “Some hope for change, some hope for the folks on campus who have been asking for that change.”

The report will outline how UP can follow through on improving and enhancing DEI on campus. Ortiz’s job now is to outline how this gets done.

“How do we move the needle when it comes to policy procedure so that we're all doing the same thing? Ortiz said, “How do we live up to our highest ideals and aspirations of the dignity of every human person?”

With that being said, she has no control over whether the Board will implement the recommendations that she gives.

“It's going to be up to the University leaders to implement ... and set up a reasonable timeline to work with the campus community to meet those goals,” she said.

Brie Haro is the Community and Engagement Editor for The Beacon. She can be reached at haro23@up.edu.