COVID-19 has wreaked havoc on schools around the nation, but as the new year begins, many classrooms are being adapted to allow in-person teaching — and UP is no exception. After a long winter break following a completely online fall semester, UP has held in-person teaching for over a month now, and it has been mostly successful, according to professors.

“On the first day, how engaged everyone was, how willing everyone was to speak up and speak to one another assuaged a lot of my fears,” David Turnbloom, assistant professor of theology, said.

UP’s partial reopening isn’t without serious considerations of social distancing and COVID-19 safety guidelines. The majority of in-person classes are taken by on-campus students, who use the Carbon Health app to track any symptoms and be notified when to stay home and quarantine.

The classrooms themselves were reconfigured with limited seating, and desks are set up with markers that indicate six feet to allow for physical distancing. Classrooms are not filled to more than 50% capacity, and each only hosts one or two classes each. Each freshman only has one in-person class to keep these numbers low. New rules also have been put in place — masks required, no eating, no drinking except for water, and, of course, follow the social distancing guidelines.

Classrooms have been de-densified to accommodate for social distancing.

This reopening was made easier due to careful preparations from last summer to make classrooms safer, according to Elise Moentmann, the associate provost. Moentmann assured that all preparations were made with public health in mind.

“Everything we've done, whether it's social distancing, or how long people are in a space, or how much time between uses, or cleaning in the evening, is all informed by the guidelines from the health authorities,” Moentmann said.

This partial reopening was also informed by evidence that classrooms aren’t the superspreaders they were thought to be at the beginning of the pandemic.

“The classroom hasn't shown itself to be an unsafe environment around the country over the last year, when people have taken all the precautions, which we have,” Moentmann said. “So that gave us the confidence to try and do this, at least in a minimal way.”

While there is always some level of concern about contracting the virus, professors appear to be comfortable with the precautions the university has put in place to keep students and professors safe in class.

“I think that my anxiety level is actually quite low,” University Provost Herbert Medina said. “All of us teaching in person got two baseline tests before we were allowed to go into the classroom. I personally feel very safe because I think we put in the right safety measures in place in order for us to carry this out successfully.”

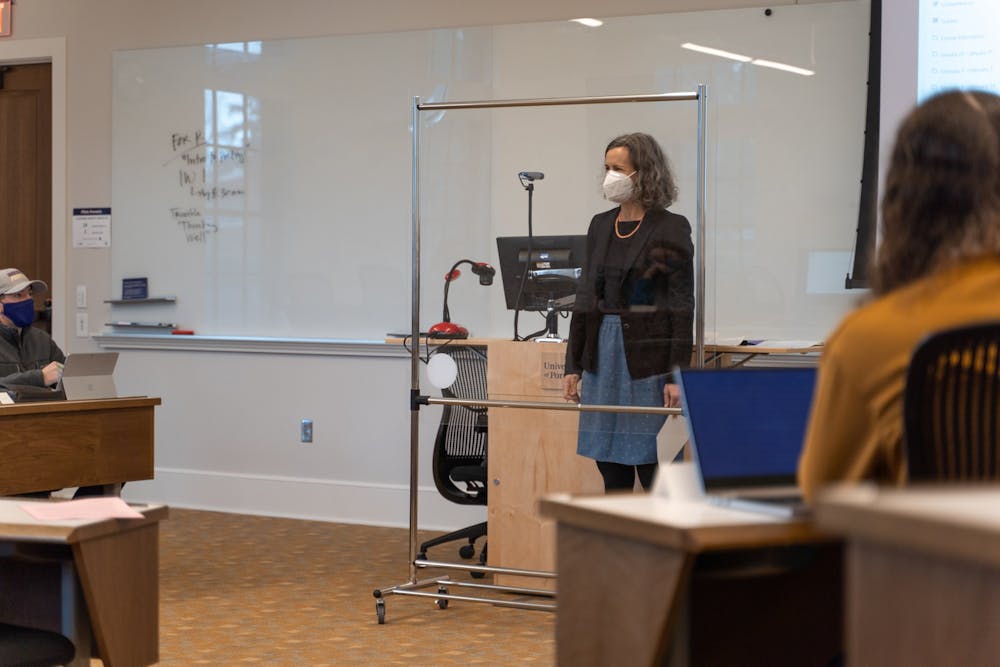

Associate Professor of English Molly Hiro lectures behind a protective shield.

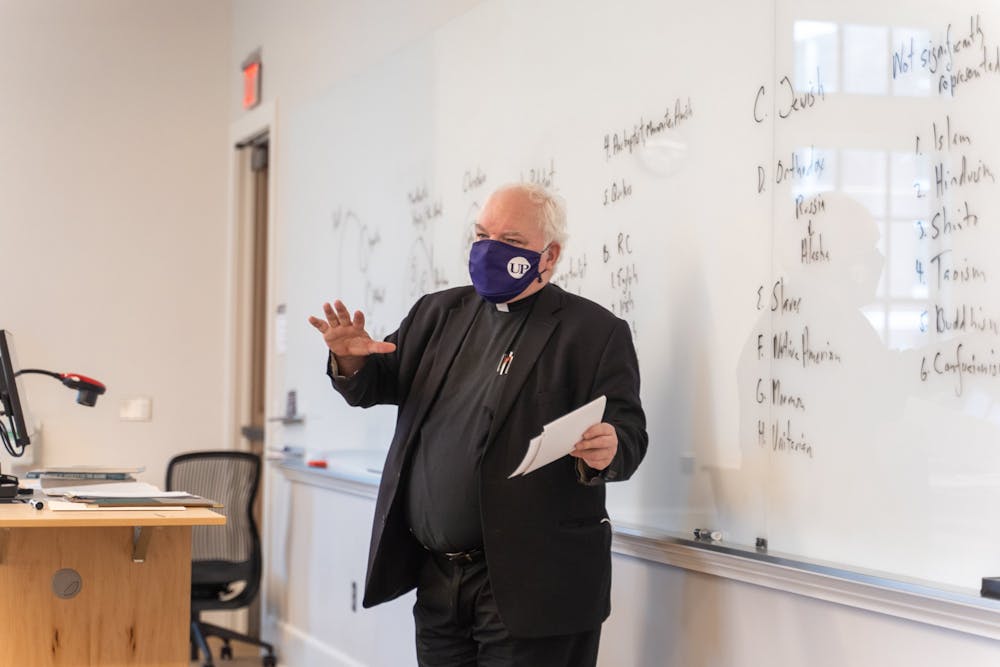

Fr. Arthur Wheeler, in his 34 years of teaching at the University of Portland, has never missed a single day of class and won’t let a pandemic keep him out of the classroom. Wheeler reports putting in up to 70 hours a week into his teaching and is energized by his time in the classroom. This is why he also volunteered to teach in-person classes alongside 33 other professors this semester.

“I intend to keep teaching as long as I can, as long as I’m able to do it,” Wheeler said.

While there are varying reasons why professors chose to volunteer, a common thread is the genuine enjoyment of seeing and connecting with students in the classroom.

Teaching a statistics course this semester, Provost Herbert Medina is one of many professors excited to be back in the classroom with students.

“I love teaching in-person, I love meeting with students,” Medina said. “It’s really, if you ask me, why I went into higher ed. It was because of the student contact. . . being able to have interactions with students on a regular basis is really exciting for me.”

Still taking into account the joys of teaching in person, other professors also weighed the risks of exposure to COVID-19. They also had to consider the potential risks it could pose to their families.

“The odds of me surviving and getting better are higher than for some other faculty, so I talked it through with my husband,” Chemistry Instructor Beth Morton said.

The risk of exposure to others was not as much of a concern for some professors, such as Wheeler, who lives alone.

“I think that students are better off to have at least the choice of doing in-person instruction. I don't have a wife or children to worry about. I'm a priest,” Wheeler said. “And I live in almost complete social isolation and I think that the precautions that the university has in place are good precautions.”

In-person teaching is an exciting opportunity for professors to part with some of the quirks of online learning, but things aren’t back to normal yet. Professors have to break some old habits, such as walking around the classroom to check on students or assigning group work, as students also must be mindful of social distancing.

“I will usually walk around the classroom talking to students, or will put them in groups, or let them eat. But I can't do that, because I can't get close enough to the students to have a conversation with them without disturbing the rest of the class,” Wheeler said.

For Turnbloom, one of the biggest challenges is not only reminding himself to stay away from the students, but also to remember that his sarcastic sense of humor sometimes isn’t as well received when students can’t see his entire face.

“I think I'm going to become a much more skilled communicator because of this process,” Turnbloom said. “I'm going to learn a whole new way of effectively communicating myself just through the tone of my voice and the words I choose, as opposed to being able to rely on my facial expressions.”

Associate Professor of English Molly Hiro, despite a few logistical hiccups, is also excited about the opportunities that in-person teaching has returned.

“On Zoom, I can't write on the board, or read body language. Those were things that I usually just take for granted about teaching,” Hiro said. “And now coming back to the classroom, there are new challenges, but there’s already just so much more of an intimacy, sharing physical space together.”

Wheeler finds it challenging to not be able to share his extensive personal library with his students, or go with them to the stacks in the library for research. However, he has found the library staff to be extremely helpful with creating online materials to support students, as well as creating more access to materials on reserve. For him, the benefits of in-person teaching far outweigh these challenges.

“What I think is really special about in-person is that I can tell just by looking at the students whether they're engaged, whether they're confused, whether they're tired. And I can gauge my response by that,” Wheeler said. “It's very difficult for me to figure out those kinds of things over Zoom.”

Fr. Art Wheeler lectures in front of a whiteboard, something many UP students haven't been able to experience in almost a year.

These interactions that are making professors feel like they are back in their environments are not only occurring with students, but also between colleagues and other faculty. Just as personal conversations would fill classrooms in the first few minutes, the professors who are in-person are able to begin reforming those same experiences in department meetings.

“There’s more space to talk to those people we haven’t seen in person. . . I’ve seen three of them in person and now we can do a little bit of chit chat before the department meeting,” Morton said.

These bits of small talk, which before may have been seen as mundane, are rekindling a sense of community amongst faculty.

The students have met this new in-person format with just as much enthusiasm as the professors. Freshman Anna Koffler was excited to find that her Spanish class just felt like a normal class, with students in desks and an engaged professor with an active presence.

“I'm glad that my in-person is Spanish, because I think learning a language online is really hard,” Koffler said. “So I'm excited to do class activities where people actually speak to each other in person.”

Koffler’s Spanish class has many of the same students as it had when they were online last semester, and seeing classmates whose appearances were normally limited to a Zoom box was surprising.

“There's a few people in that class that were in my Spanish class last term, and you feel like you know what they look like over Zoom, because you can see their full face,” Koffler said. “But in person with the masks I’m like, ‘you don’t look like what you used to look like!’ So I thought that was funny.”

With the announcement that UP’s fall 2021 semester will be primarily in-person, professors and students are optimistic that this semester will lay the groundwork for more success.

“I'm hopeful, because there are a whole lot of things that happen at UP outside of the classroom that are just as important as what happens inside the classroom — the Residential Life programs, the things that the Moreau Center does. . . things that aren’t just auxiliary, but I think crucial to the type of education formation that UP does amazingly,” Turnbloom said.

Professors that utilized prerecorded lectures while teaching online are excited to be able to focus on active learning methods rather than spending time on recording and preparing delivery methods.

“Recording all of those videos was a large amount of my time,” Morton said. “I didn't, you know, aim for perfection, but I wanted them to be coherent — something that the students were going to get something out of and not just be sitting there watching. And so, kind of that recording piece is something that I don't miss.”

Bundled up with the excitement of returning to an in-person format and moving past teaching from home, professors also have more specific moments that stem from in-person class that they look forward to having again.

Instances like these include sparking conversations from walking around the classroom and peering over the shoulders of working students, as in Medina’s case. Another being the joy of getting to high-five a student when a concept is finally understood after hard work, which was something Morton enjoyed doing in her classes.

Though Medina and Morton realize they still can’t do these things during in-person classes yet, they are hopeful for a time in the future when they can. For now, the satisfaction of seeing students’ faces in the classroom is plenty.

“It makes me feel like I’m back where I’m supposed to be,” Morton said.

Professors weighed many factors while deciding whether or not to volunteer to teach in-person this semester. What brought them back on campus were the opportunities to make connections with students and colleagues. These connections and relationships bring professors the joy and excitement that tells them the classroom is the right place for them to be.

Laura Heffernan is a reporter for The Beacon. She can be reached at hefferna23@up.edu.

Sadie Wuertz is a reporter for The Beacon. She can be reached at wuertz22@up.edu.