On a Friday night roughly 15 years ago, Portland Pilot Megan Rapinoe scored two goals in the Women’s NCAA Soccer Tournament quarterfinal and predicted her future. In her own words, “When we won 3-1 that night at Merlo Field, we were so over the moon you would think we had won the World Cup.”

Nearly a decade later, on her 30th birthday, Rapinoe celebrated with her teammates on the field after winning the 2015 Women’s World Cup.

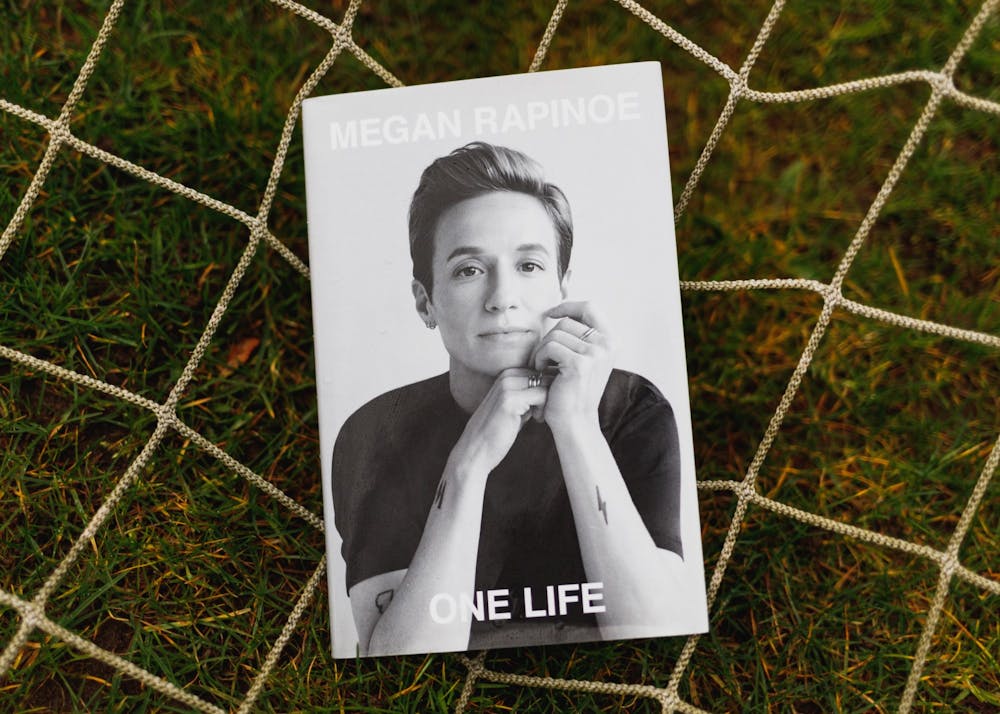

But that’s not the whole story. In fact, 35-year old Rapinoe’s recently published memoir, “One Life”, focuses more on her transition from insouciant soccer player to a conscientious athlete using her platform to promote activism — mincing few words along the way, telling the reader that “Given the breaks I’ve had, speaking out seems like the least I can fucking do.” This 240 page story is one of extraordinary skill meeting extreme dedication, and by the end of the book, Rapinoe burns one question into readers’ minds: what are you going to do with your One Life?

Rapinoe traces her athletic and activist aspirations back to her childhood in a rural town near Redding, California. Growing up, she quickly became a soccer standout, first playing on an all-boys youth team because it was the only local team. Even now, having won the 2019 Best FIFA’s Women’s Player Award, Rapinoe writes that she has “probably never dominated a team like I did that team of small boys in the early 1990s.”

From that first season, Rapinoe and her twin, Rachael, lived and breathed soccer, and she makes that overly clear, with little of her adolescence mentioned outside of the sport. For years, every Saturday started at four in the morning with packing cleats and socks into the minivan and driving hours to train with their team. And Rapinoe thanks her parents for never forcing her to play the sport that she loved — and still does.

Although, such as myself, some readers might struggle to relate to or connect with the superstar through most of the book, the chapter titled “Brian” will hit close to home for many. Rapinoe tells the reader of her brother’s increasing addiction to opioids, leading to years of on and off incarceration. Regardless, Rapinoe takes a wise and forgiving approach to covering this sensitive subject, writing that “It’s one of the misconceptions about drug abuse that it only strikes those who are unhappy, or misfits, or from terrible homes — all dumb cliches, none of them true. You can’t tell by looking at someone, or their family, if they’re likely to use drugs, and when Brian was clean, he was amazing.”

Here, the reader is finally able to access a more vulnerable side of Rapinoe — a focus outside of soccer or activism. But Rapinoe is far from normal, as shown in her college recruitment process. By the end of her high school career, Rapinoe had drawn national attention from college scouts. In 2003, she visited the University of Portland with her sister, and to both of their surprise, they instantly fell in love. Rapinoe writes that they “both lost their minds,” and immediately knew that they had found their home for the next four years, citing that “The soccer team was cool, the field was amazing, Portland was perfect, and the college vibe jibed with what we were looking for.”

For most 19-year old competitive athletes, playing at a D1 school on a full scholarship is as good as it gets. But for Megan Rapinoe? It would only be the beginning.

After winning the NCAA Championship her freshman year, Rapinoe seemed unstoppable, netting 10 goals in 11 games for the Pilots in her second year. However, she tore her ACL before the playoffs, forcing her to miss the season and her shot to play in the 2017 FIFA World Cup.

Although Rapinoe discusses this period of her life as an anxious and dark time, her hyperfocus on soccer in this part of the book seems to detract from her immense growth in other areas. For the first time, she informed herself of social justice issues and realized just how politically liberal she was, despite her conservative upbringing. Furthermore, she realized in the middle of a practice that she was lesbian.

“It wasn’t like, oh, suddenly I’m gay,” Rapinoe writes. “It took a second to figure out what was going on. But while it was happening, it didn’t feel negative. It was just . . . normal. For the first time, I was attracted to someone, and the discovery thrilled me. All those years of missing out, of not feeling what everyone else seemed to be feeling and having no idea why, were over, and any regret I might have experienced about those feelings being for a woman were overwhelmed by a sheer sense of relief.”

Rapinoe doesn’t dwell too long on this point, choosing again to focus on her soccer career, though her personal time at UP might be more interesting to readers such as myself. She would return to the pitch after yet another ACL tear, and despite missing no shortage of games and only playing three seasons, remains the Pilot’s 10th highest scoring player in history.

What follows this chapter of Rapinoe’s life is several years of half-serious relationships, transfers from one professional team to another (including two seasons in France), and dozens of awards. But that’s not what she cares about, and that’s not what makes her so interesting. No, not even her 2015 and 2019 FIFA World Cup Championships or her 2012 Olympic gold medal.

Megan Rapinoe stands out on the field because of her athleticism and vision, but off of the field, that’s where she does the real work. In 2016, she took a knee during the national anthem of an international game — becoming the first major white athlete to follow Colin Kaepernick's kneeling in protest of police brutality and institutional racism. After the game, Rapinoe told a reporter “It was a little nod to Kaepernick and everything that he’s standing for right now. I think it’s actually pretty disgusting the way he was treated and the way that a lot of the media has covered it and made it about something that it absolutely isn’t.”

It’s clear to me that Rapinoe isn’t in it for the money or the fame — even after death threats and pressure from fans to stop, Rapinoe has only focused more of her attention on activism, using her platform to draw attention to major issues. In 2019, Rapinoe and several teammates filed a lawsuit against the United States Soccer Federation demanding equal pay as men, an effort that she spearheaded after seeing how much more the men’s national team was earning, even with a much worse record.

Rapinoe has also been outspoken as a member and ally of the LGBTQ community, giving speeches at conventions, donating and supporting the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network (GLSEN), and much more.

Today, Rapinoe continues to play as a winger for OL Reign based in Tacoma, as well as maintains her consistent spot on the Women’s National Team. She is engaged to WNBA player Sue Bird, and continues to raise awareness for a broad range of nonprofit organizations and social issues.

Readers get to witness Rapinoe’s growth from a small conservative town to athleticism and activism at the highest level, right alongside a crash course in professional soccer, politics, and much more. Given the amount of information condensed into one memoir, it’s no surprise that we don’t get too much insight into her emotional side. Rapinoe doesn’t let her personality reveal too much through the page, but that’s okay, because she’s the perfect exemplar of “actions speak louder than words.” Realizing that she is in a position of privilege, Rapinoe wants to help others as much as she can, and I can respect anyone with this sentiment.

Megan Rapinoe is here to stay. She knows we can do better and shows readers that it isn’t that difficult to do the right thing. In Rapinoe’s own words, “People want to stay asleep and say, Oh, I don’t understand what’s going on. Well, read a fucking article.”

Carlos Fuentes is the copy editor of The Beacon. He can be reached at fuentes22@up.edu.