It was December of 1955 when UP junior Arlene Goetze was alarmed to find her doppelganger hanging irreverently on UP’s hallowed grounds. The effigy, a puppet constructed by the ROTC to look distinctively similar to Goetze, was hung in protest of a cartoon she had published in The Beacon just a short while before. The first female Editor-in-Chief of The Beacon, Goetze was used to notoriety — but never like this.

“That was the first thing in my life that really impressed upon me the power of the written word,” Goetze said. “Just a few could make a group of men pick on a girl and hang an effigy.”

Now 85 years old, Arlene Goetze is living in Silicon Valley with her husband, another UP alum, and it’s clear that she has never forgotten what words can do. Goetze’s extensive experiences of writing and exploring spirituality as a Catholic woman culminate in her latest book, “Exploring Spirituality in Photo & Verse.”

Arlene Goetze, first female Editor-in-chief of The Beacon, poses for a portrait. She has multiple published works from her extensive career in journalism and beyond.

Photo courtesy of Arlene Goetze.

“You never really know the power of your words when you're writing,” Goetze said. “They can change something quite, quite dramatically.”

It all started at The Beacon, where she was appointed first female Editor-in-Chief on May 25, 1955. Goetze also worked as the co-editor of the LOG at the same time. The picture that Goetze painted of UP in the 1950s created a stark contrast from partially-online UP in 2021. When Goetze was there, UP had just only recently allowed women to attend the university — prior to this, it was a mens only college. She described dances or balls where girls would be voted on as princesses or queens, and a Sadie Hawkins dance she remembered going to in 1956.

But besides the social factor, working at The Beacon was a very different job. Goetze served as co-editor alongside another student named Ed, whom she described as being the stereotype of a scoop reporter in a film. She detailed the process of sending copies of the Beacon off to the printer to be type set, going to the printer to proofread it, and then waiting to proofread again after the printer would change the type for every single mistake.

The paper itself also looked quite different — almost every page featured an ad for a cigarette company.

“The Lucky Cigarette ads would always have doodles, so you would doodle on the ad and remember the name,” Goetze said.

When she published the cartoon that ended up causing her to be hung in effigy, she already had plenty of experience working on the paper, and was more surprised and amused than anything else. According to Goetze, the cartoon was a reaction to a ROTC event where they had claimed only soft drinks were enjoyed. After the event, it was made clear that that wasn’t true.

“They had told us that they were serving only soft drinks, but then they were going around campus giggling all over the place because they had been drinking something they shouldn’t have,” Goetze said.

She pulled out an old cartoon of a girl talking to a clearly hungover boy, and changed the caption to say, “You must have had some of the soft drinks at the Arnold Air social!” After she published the cartoon, ROTC immediately took offense to it, constructed an effigy of Goetze and hung it. This was a harsh response that Goetze didn’t seem to take too seriously; she laughed as she talked about it.

A cartoon poking fun at UP’s ROTC program displays a person, drunk, after drinking the soft drinks at the Arnold Air social. The cartoon ultimately led to ROTC burning an effigy of Goetze.

Photo Illustration by Brennan Crowder

After graduating from UP, Goetze married a fellow UP alum, who had, ironically, been a part of ROTC — but in the years before the effigy. She then went on to work for one of Oregon's most notable governors, Tom McCall. Along the way, she and her husband had seven children, and her husband’s job took them to Washington D.C., where he worked in the Pentagon.

They then moved to Silicon Valley, where Goetze began her work with the Catholic church. She worked with the Bishop in the Diocese of San Jose, running communications, and after a few years of that, she moved into working more independently: writing church histories, consulting and eventually starting a nonprofit Catholic newspaper.

“It just accidentally happened,” Goetze said. “One day I just thought, well, we'll gather the women and the Diocese together. And we had 100 women show up for two events, so I started a little newspaper.”

Goetze stumbled upon the business of running a non-profit accidentally too.

“One day, a nun, who makes no money, came up and gave me $10 for the paper,” Goetze said. “So I thought, ‘Oh, we have to become a nonprofit.’”

The newspaper, Catholic Women’s Network, featured a variety of columnists from wildly divergent backgrounds. According to Goetze, at one point the paper featured two college professors along with two women serving life sentences in prison.

“Neither one attended high school, but the columns they wrote were exceptionally deep spiritually,” Goetze said.

Goetze explained that the newspaper, though it was a nonprofit, had enough money from donations to pay the columnists. She remembered one particular instance where she got a phone call from a prison in New York.

“People from the prison called me because I had sent him a $10 check, and they wanted to know if I really sent that check,” Goetze said. “They wouldn't believe that I had sent the check to this man, because what’s a man in New York State doing reading my little paper on women's spirituality?”

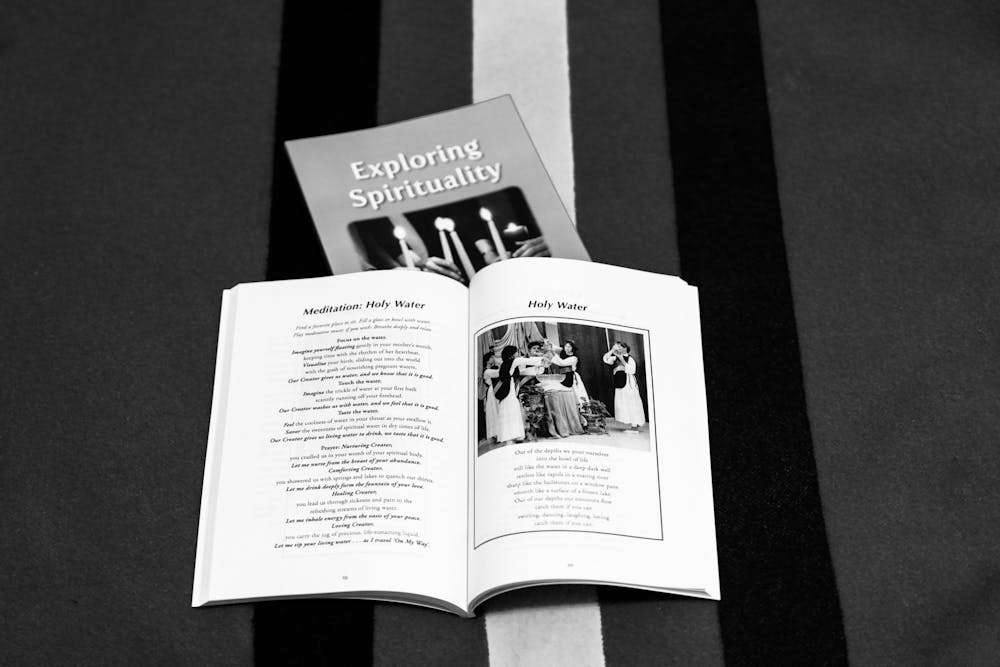

"Exploring Spirituality in Photo & Verse" displays a poem accompanied by a picture written and photographed by Arlene Goetze. Goetze is the first female editor-in-chief of The Beacon.

Photo Illustration by Brennan Crowder

Spirituality, particularly feminist spirituality, is central to Goetze’s life and career. The Catholic Women’s Network was largely centered around the uniquely female experience of Catholicism and Catholic spirituality.

“We did not use the term of God in the male,” Goetze said. “We weren't against the church, it was not negative. We were just trying to enhance women's gifts. It was an aspect of spirituality that we felt had been missing in the past.”

Her strong ties to faith and spirituality are central to her writing, especially her tenth and most recent book, self-published just last year. “Exploring Spirituality in Photo & Verse” sets poems and photographs in conjunction with each other to form a unified representation of a virtue. Goetze is interested in the spirituality of some of the simplest things in life.

“What's the virtue of a woman eating an apple?” Goetze said. “What's the spirituality of the apple?”

Earl Goetze, Arlene Goetze’s husband, describes her as nonstop — always writing, working, and taking care of their family.

“We moved a few times, and she was always so efficient,” Early Goetze said. “We would move to a new place, and after a week and a half, she would already have it fixed up. And that's the way it was.”

Arlene Goetze is certainly nonstop. She has thus far lived 85 years of a lifetime sparked by The Beacon: working, making achievements as a woman, and, most importantly, writing.

“All I ever wanted to do was to write,” Goetze said. “One of my teachers used to tell me daydreaming was useless. I daydreamed all the time. I thought it was a great skill.”

Sadie Wuertz is a reporter for The Beacon. She can be reached at wuertz22@up.edu.