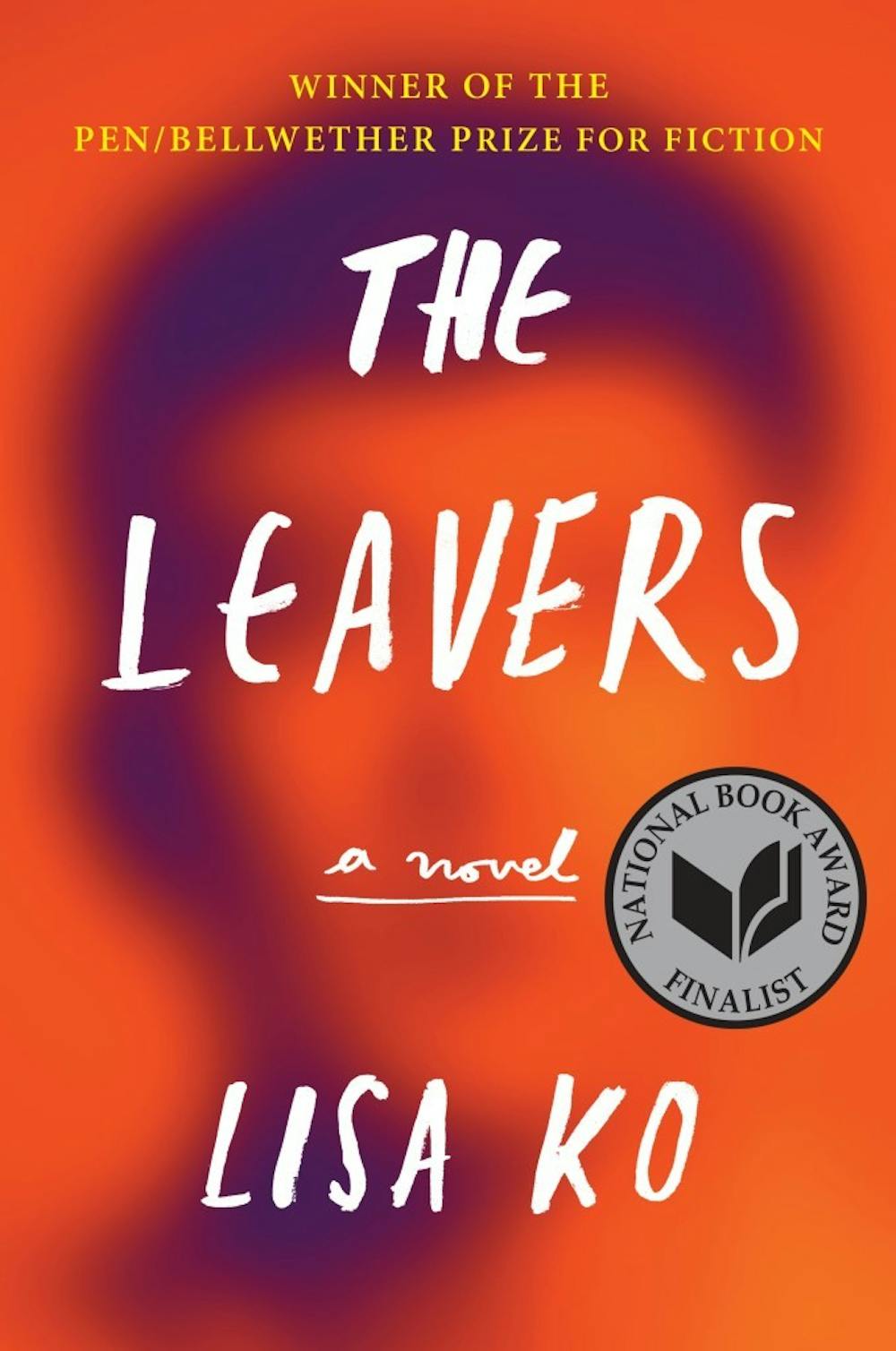

On Monday, Feb. 10, Lisa Ko, author of this year’s ReadUP selection “The Leavers,” will speak in Buckley Center Auditorium. The novel centers on Polly, an undocumented immigrant from China who works in a Bronx nail salon and one day disappears, leaving her 11-year-old son, Deming, behind. The story, also the winner of the 2016 PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction, touches on themes of family, immigration and identity.

Ko’s talk will take place in BC Auditorium on Monday, Feb. 10 at 7 p.m., with doors opening at 6:30 p.m. and a book signing happening after the event. No tickets are needed.

On Monday, Feb. 10, Lisa Ko, author of this year’s ReadUP selection “The Leavers,” will speak in BC Auditorium. Photo courtesy of Lisa Ko.

In a phone interview with The Beacon, Ko explained what inspired her to write the book, how she developed her characters, and her writing process.

The Beacon: You say that growing up, you “were a good observer and a better spy?” What do you mean by that, especially the “spy” part, and how does it inform your approach to writing?

Lisa Ko: I’m an only child, so I definitely grew up watching my family and was also the only grandchild for a long time. I had a lot of opportunities to watch back before the internet, so I really kind of watched my family around me. And I also watched (my classmates), as one of the only non-white kids in my school, so there were a lot of opportunities to see how people interacted and to observe relationships and different maybe even class and racial signifiers and learn from that and the language of how people acted and behaved around another.

The Beacon: Tell us about the article you read that inspired the book and why this story, in particular, remained with you in such a particular way?

Lisa Ko: The article was about an undocumented Chinese woman who’d been imprisoned in an immigration prison and separated from her son, and her son was adopted by a Canadian family. It kind of led me down a path of researching and learning about other cases of parents being separated from their children.

I was able to situate it in a long history of family separation in the U.S., and I was wondering why these stories weren’t being seen more prominently in mainstream media, and there just seemed to be something fundamentally unjust about family separation and how it exerts dominance over people. I was also very curious about why these children had to stay in the U.S. and be adopted by mainly white families with more economic status and why the parents had to leave.

The Beacon: When the article came out, family separation wasn’t in the news as much. Would that have changed how you had written it, or how has the reception of the book been different since then?

Lisa Ko: I don’t think it would’ve changed how I’d had written because the characters and the story itself are something that existed apart from the article, and it grew from there. I think it’s been interesting how these stories have become more prominent when they’ve really been happening since the beginning of the U.S. itself, and we’ve seen it going on for centuries. But now, we have this administration, where it’s very proud of these atrocities, whereas maybe in the past, it was more slightly undercover.

The Beacon: In 2014, you set a goal to get 50 rejections a year. Why that goal, why that number, and how did “The Leavers” end up getting published from that goal?

Lisa Ko: It was a way to do some reverse psychology on myself. As artists and writers, we have to send out a lot of work for publications and apply for fellowships and residencies, so it’s easy to get really discouraged when you get inevitable rejections. I tend to work well when there’s a bit of competition and goal setting, so figured if I set this number — which, 50 was a very arbitrary number that seemed almost absurd. More than 10 and less than 100. And by aiming for more rejections, I was forcing myself to send out more work, and for every rejection I received, while I inevitably became more disappointed, it was sort of like a small victory, because I was one rejection closer to that goal.

It did work, and I didn’t really end up getting to 50, but I ended sending up more work than I had in previous years. I got more rejections, and I also got more acceptances, so it’s very much a numbers game. I ended up applying for an award called the PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction, and it was an award given to an unpublished manuscript. I was trying to bump those numbers up and decided to submit a manuscript. I never thought I would win, but I was shocked and pleasantly surprised to find out I did several months later.

The Beacon: So, the book is told from the perspectives of multiple characters, Deming, the son, and Polly, the mom. Why those narrative choices of alternating perspectives in that way?

Lisa Ko: It was really the result of a lot of trial and error. I started the book in 2009 as having it slowly be in Polly’s voice, but I realized I couldn’t really tell her story without telling her son’s story, and that relationship and that separation really intrigued me. I started writing from Deming’s perspective, just to learn more about his character. That’s when I realized what this story was about — these two characters coming to terms with their separation and their relationship and Deming’s search for his mother.

I experimented with all of these different possibilities of writing from alternative perspectives using first person and third person, and it turned out that was really just the combination that ended up working for the story, having Deming as a young adult start looking for his mother and then his mother telling her side of the story as well.

The Beacon: Polly is an imperfect mom, and an imperfect immigrant mom at that, a figure we often see idealized, usually by immigrants and immigrant kids ourselves. How does a character like this counter the typically idealized/demonized versions of immigrants we usually see and allow for fuller conversations about immigrants?

Lisa Ko: I think I’m just really interested in writing characters that feel real to me. This idea of the perfect mother or the perfect immigrant mother doesn’t exist in real life. Nobody’s perfect, and nobody can live up to those standards. And those standards are often couched in sexist ideals about women and motherhood.

I wanted to write a character that was three-dimensional and complicated, in the way that people are in real life. Those are the stories that are the most interesting and fulfilling to both write and read. It really came out of imagining what personality traits it would take for this young woman, Polly, who’s really in her teens, to come on her own to this new country, where she doesn’t speak the language or know anyone, and the determination and the stubbornness that that kind of person would have and building those traits into that character.

The Beacon: How does your book speak to the rifts that sometimes appear (or disappear and reappear) between immigrants and their children who are born or who grow up in another place?

Lisa Ko: It’s a very specific story between one particular mother and son whose experience is very atypical, I think, to an immigrant story, but I think the themes of wanting to know where you came from, of wanting to find a sense of belonging and home and family, whatever those things might mean, both in a physical sense and a psychological level, are things that resonate across many families and generations.

The Beacon: Moving on to Deming’s later life, he’s adopted by a well-meaning white liberal family that is not prepared to parent a child of another race, especially when he’s the only Asian student at his school. What is the book’s message to well-meaning but harmful white people, and was it informed by your own experiences growing up in a largely white community?

Lisa Ko: I don’t think I necessarily wrote it with the intention of sending a message to the parents. I just was very interested in speaking about the experience of Deming as a character and thinking about the children of the parents I read about in the article who were separated and grew up in communities where they were often very isolated and what it was like for them.

It speaks of centering the stories of those children, and the importance of transracial adoptees, I’m not one myself, but to center their stories and to hear them. While Deming’s experience is very much different than mine, there was some of that emotional strain of isolation and alienation that I definitely related to with my own childhood.

The Beacon: You have been journaling and writing stories since you were five years old, and you’ve said that you write for your younger self. What exactly do you mean by that, and why is it so important?

Lisa Ko: I think about how, when I was younger and growing up feeling that sense of isolation, how reading books was really a way to to give myself hope and also a path into possibilities for myself, and an understanding of who I was and the people around me and who I could be. (I also think about how) pretty much no books were written by Asian American authors and featuring Asian American protagonists and how meaningful it was to finally see that. I think about the importance of telling stories where these characters and values are centered. How important it is not only for readers of all ages but for writers ourselves.

The Beacon: Will there be certain aspects of the story or of the writing process you’ll focus on talking about when you visit UP?

Lisa Ko: I love talking about both the writing process and the story. I think that it’s often kind of inseparable. Why do we choose to write or gravitate toward the stories we’re interested in are things that feel very related to one another.

Dora Totoian is a reporter and the Opinion editor for The Beacon. She can be reached at totoian20@up.edu.