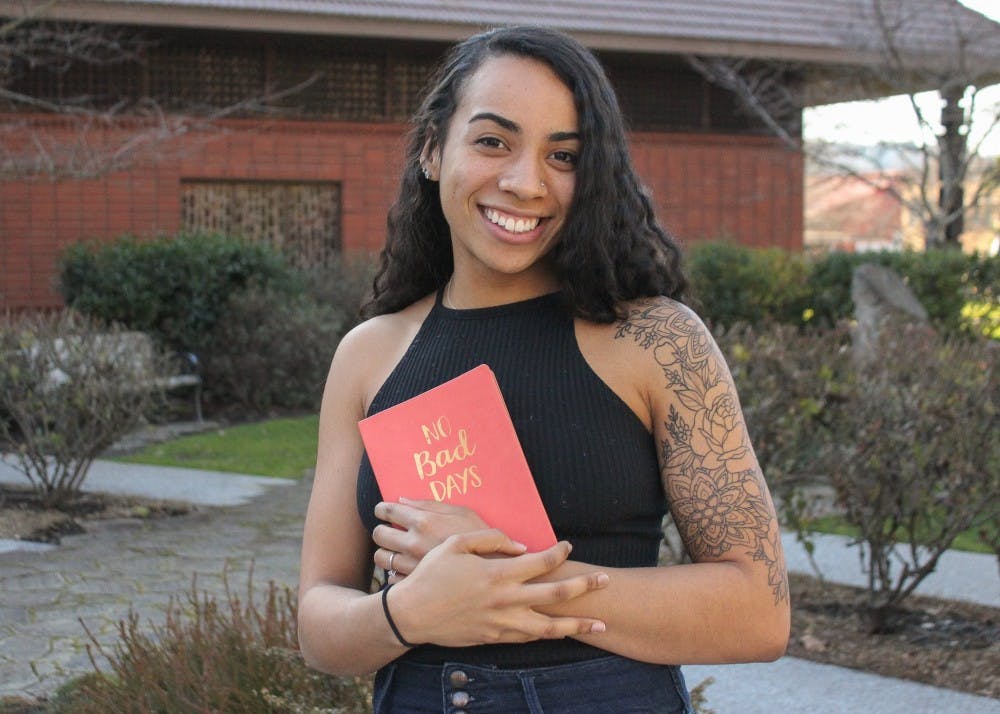

It started as a New Year’s resolution her junior year of high school. Cutting out certain foods from her diet seemed like a good way for junior theater major Maddie Nguyen to turn her life around. She was dealing with what she now recognizes was depression, and she wanted to do something to make her life better. She started to lose weight and she enjoyed the responses from others who noticed.

“When other things in my life weren’t going so well, that was the one thing I could control,” she said. “So it started spiraling into ‘can’t eat those foods,’ ‘can only eat in this portion of the day.’”

After her diet became more extreme and physically harmful, Nguyen was hospitalized and diagnosed with anorexia nervosa.

This week is National Eating Disorder Awareness Week, which serves as a reminder that Nguyen’s story is not uncommon among Americans. Eating disorders take many forms including anorexia, bulimia and binge eating.

According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, 30 million people of all ages and genders in the United States suffer from an eating disorder, and every 62 minutes someone dies as a direct result of an eating disorder.

Eating disorders affect both physical and mental health and can stem from a variety of emotional or environmental stressors.

After spending two weeks in the hospital, Nguyen was forced to take a semester off of school and go to clinical therapy to recover. During her six months at the clinic, she was not allowed to throw any food away.

“Every time I ate, I had to close my eyes,” Nguyen said. “I could not get through a meal with my eyes open because I just didn’t want to accept the fact that I was putting things in my body that I felt were making me fat.”

Health and Counseling Center staff counselor Alysa Romano said that therapy can be a good way for students suffering from an eating disorder to explore and understand what from their history has lead them to this eating disorder. Therapy can also be a safe place for students to talk about an eating disorder if they are not comfortable telling their family or friends who may not have any idea what they are going through.

“Looking at someone could tell you virtually nothing about their health,” Romano said.

Even though she considers herself to have recovered from the eating disorder, Nguyen believes that her experience with anorexia is going to be something that stays with her for the rest of her life.

“Recovery isn’t a switch you flip and then suddenly you’re all recovered,” Nguyen said.

While her time at the clinic helped her to get better, Nguyen believes that participating in theater is what has been the most helpful for her recovery.

“Eating disorders are very much a way of putting up walls and protecting yourself from the rest of the world,” Nguyen said. “And in theater, you have to be vulnerable to be good.”

Nguyen is not alone in her struggle with anorexia. According to the National Eating Disorders Association, one study found that between 0.9 percent and 2.0 percent of females of all ages will develop anorexia.

If someone is questioning if they have an eating disorder, wants to seek help, is in the process of recovering or has recovered, there are resources available to them on campus.

“We want to be here and be available to meet students where they’re at,” Director of the Health and Counseling Center Carol Dell’Oliver said.

The Health and Counseling Center can diagnose eating disorders based on certain criteria. According to Dell’Oliver, some criteria that would be looked at would be the diagnostic and statistical manual for mental health disorders, the student’s own story and other medical criteria.

“When I do the exam, we’re checking lab work, and we’re running an EKG, looking at urine tests and then just doing a comprehensive physical exam,” Courtney Rau, FNP-C and associate director of primary care services, said.

Rau said that some common physical symptoms she has seen are fatigue, dizziness and heart palpitations.

The Health and Counseling Center offers treatment for mild to moderate cases of eating disorders and will provide students with referrals to outside medical providers or treatment centers for more moderate to severe cases on top of counseling services.

Rau stressed that the process of diagnosing and treating a student with an eating disorder is an “interdisciplinary process” between counselors, nutritionists and medical practitioners.

But not all eating disorders are formally diagnosed. Junior mechanical engineering major Alexis Peltier never went through the process of being diagnosed with an eating disorder by a medical or mental health professional. She still knew she was suffering from one.

Having anorexia was not something she vocalized. She was an athlete. She burned a lot of calories at swim practice. She was more or less a healthy high school student.

Then Peltier became self-conscious. She did not want her thighs to rub together when she ran. She started limiting what foods she could eat. She started losing hair. Her hips started clicking when she walked. She avoided social gatherings whenever food was involved. Peltier was exhibiting typical symptoms of someone suffering from an eating disorder.

Peltier tried to mask the eating disorder with different diets. She told people that she wasn’t eating anything with added sugar or she would say she didn’t eat anything unhealthy because she didn’t want people to ask her why she wasn’t eating.

For Peltier, the drastic change in her weight and the physical symptoms of the eating disorder motivated her to get better.

“I didn’t ever want to be in a situation where I wasn’t able to do something because of my physical ability,” she said. “And I knew not eating enough was causing long term damage to my physical health...I wanted to be stronger.”

During her recovery, she became vegetarian, which helped her to have some control over her food while also eating a healthier amount. The final step of recovery for her was talking about her experience with anorexia.

“Once I was finally able to speak about it and continuing to talk, I think the further removed I became from my eating disorder and was able to separate that and break out of that,” she said.

Even though eating disorders can be overcome, recovery is not always easy. Like Peltier, senior civil engineering major Amber Rose has also suffered from anorexia. For Rose, anorexia has been something that she has struggled with since eighth grade and still continues to battle with today.

Rose has participated in residential treatment three times and has had to take time off of school as a result. Her freshman year at UP, she made the decision to quit the cross country team because her physical health was so poor.

Her first time at treatment was her senior year of high school when her parents forced her to go. The next two times, her freshman and sophomore year at UP, Rose made the decision herself to get help.

“The second time I went to treatment, I actually chose to go to treatment,” Rose said. “That was kind of powerful for me to actually choose to be there and I think at that point I just had no energy and no social life...I kind of just reached this point where I knew I needed help.”

Although treatment has been helpful, Rose does not consider herself to be fully recovered. She said it was difficult for her to feel like treatment did not work the first time, but she still believes in the process and would recommend treatment to anyone suffering from an eating disorder.

Rose’s story is a reminder that treatment is not an easy process, but it can ultimately be a positive resource for someone struggling with an eating disorder, even if it takes more than one try.

“There’s an impression that treatment is really ineffective and that recovery is really really low and I think that’s not always true,” Romano said.

Romano added that treatment can be especially effective if it is started during the early stages of the eating disorder.

Even though Rose has not recovered completely, the connections she has made in college have helped her and given her people she can confide in.

“I think something that has been really powerful in recovery is making those new connections and just feeling connected to campus now,” Rose said.

While Nguyen, Peltier and Rose have struggled with anorexia, it is not the only prevalent eating disorder that many people suffer from. According to the National Eating Disorders Association, one study found that between 0.2 percent and 3.5 percent of females will develop binge eating disorder.

For junior nursing major Christina Spires, the idea of eating large quantities of food was a part of her family and culture. Spires said that her Pacific Islander and African-American heritage led to her family eating a lot during social gatherings.

“I knew that it wasn’t okay that I was eating that much but it was like ‘what am I going to do?’ so I kind of just kept eating and got into a vicious cycle,” Spires said. “When I decided that I wanted to make a change because I was also a student athlete, I didn’t know how to do that so I just thought I had to restrict what I was eating very harshly.”

Dell’Oliver said that the role of food in someone’s life often changes as a result of an eating disorder.

“There’s a relationship with food that needs to be explored,” Dell’Oliver said. “Food can be a source of nutrition and a way to promote self care in that it provides you with the energy that you need but with people with more significant eating disorders, their relationship with food has taken a turn and it may not mean those things to them...there’s a redefining of their relationship with food that needs to be addressed and reshaped over time.”

Spires first saw signs of the eating disorder in eighth grade. She was used to eating a lot with her family but this turned into binge eating on a regular basis. After a binge eating episode, she would feel guilty and compensate for the bingeing by purging or restricting her food consumption.

Purging disorder is commonly known as eating large amounts of food and then repeatedly causing self-induced vomiting, consuming laxatives or diuretics or enemas.

Talking to her boyfriend has been the most influential part of the recovery process for Spires. She said his support and motivation have helped her to overcome her eating disorder. She journals most days and checks in with herself about how she feels and she has been able to recognize what feelings trigger the want to binge eat such as feeling stressed or tired.

For Spires, becoming her “own best friend” has proven to be effective in her recovery. She also said that realizing that weight is not as big of a deal as she used to think has been a big part of her recovery.

“Having different measures of health and happiness need to go beyond the scale,” she said.

In honor of Eating Disorders Awareness Week, the Health and Counseling Center is holding an event to encourage healthy eating. “Mindful Eating — Food as Medicine” will be Thursday, Feb. 28 at noon on the quiet side of The Commons, and will be lead by School of Nursing Professor Tanya Bachman who will discuss the importance of taking care of the body using food.

Dell’Oliver said that if a student, faculty member or family member is concerned about a student’s eating habits, they should have an honest conversation with them. If they are still concerned, they can contact Early Alert by calling Gina Loschiavo at (503) 943-7709 or filling out an online form describing the concerning behavior of the student.

National resources are also available to anyone struggling with an eating disorder. The National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) has a helpline, (800) 931-2237, and a screening test available. NEDA can also help find treatment centers based on location and need.

Madison Pfeifer is a reporter for The Beacon. She can be reached at pfeifer21@up.edu.