One University of Portland student was only eight when she had her first scare with immigration officials.

She remembers a day in the Safeway parking lot when she saw “the van”. She ducked her head, kept quiet and stayed down as her mother drove the car home, avoiding the immigration agents.

If caught, her whole family would be deported.

They made it home that day. But their experience was a stark reminder that they had a secret to keep: They were undocumented immigrants.

The Beacon has agreed to use the pseudonym Julia Ortiz for the safety of the student sharing her story.

Ortiz was born in Mexico and has lived in rural Oregon since she was 2 years old. Her parents came to the U.S. looking for jobs; her father became a farm worker and her mother a waitress. She and her family lived in a single-room storage garage in her uncle’s back yard until she was five, and have lived in a small apartment ever since.

Ortiz fights back tears as she recalls her past. This is only the third time she’s told anyone she is undocumented.

“I learned that I couldn’t tell anyone where I was born pretty young,” Ortiz says. “When people would ask, my parents would say, ‘Tell them you were born close by here.’ I’ve had friends for years and never was able to tell them where I was really from.”

Ortiz is just one of the students on The Bluff who is able to attend UP because of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy, which former president Barack Obama began in June 2012. Through DACA, Ortiz and 700,000 other children of immigrants in the U.S. have been granted deferred action from deportation for two years, which they can renew, but it is not a path to citizenship and does not grant them lawful status.

Ortiz says she was lucky to be accepted to the DACA program. There are strict residency requirements for DACA and many young people are denied. Many people are deterred by the $465 application cost, and renewing it every two years has the same hefty fee. Some also fear increased risk of deportation if they apply and the rules change later, especially under the new Trump administration.

The lengthy process caused Ortiz to submit her application to UP a month past the admissions deadline and she doubted whether UP would accept her because of it. She made plans to attend the community college near her home instead.

But teachers from her high school believed she could go further. They directed her toward scholarship applications and proofread her essays.

“Literally by God’s hand, I am here,” she said.

Ortiz said she chose UP because the staff was so supportive of her.

“I let [UP] know of my situation, and the people here helped me so much and they let me know that they really care about my education,” Ortiz said.

“The only reason I’m here is because there are so many people that are out there that really do want to help. And knowing that is the best feeling; knowing that people want you to go further, even though you’re in an illegal situation. It’s literally a miracle that I’m here.”

On the campaign trail President Donald Trump pledged to undo DACA, though exactly what his long-term solution will be for those who are on DACA is still unknown. If he does repeal it, however, Ortiz could face deportation, which she says is scary to think about.

“Right now the only thing that’s keeping me from worrying about that is knowing that I’m here now and I need to worry about what I’m doing now, and if something does happen, then we will find another way and we will work on it,” she said. “It’s a scary idea, knowing that that can just be taken away so easily.”

Being raised in the United States nearly her whole life, she says it is hard to believe that she is “illegal”.

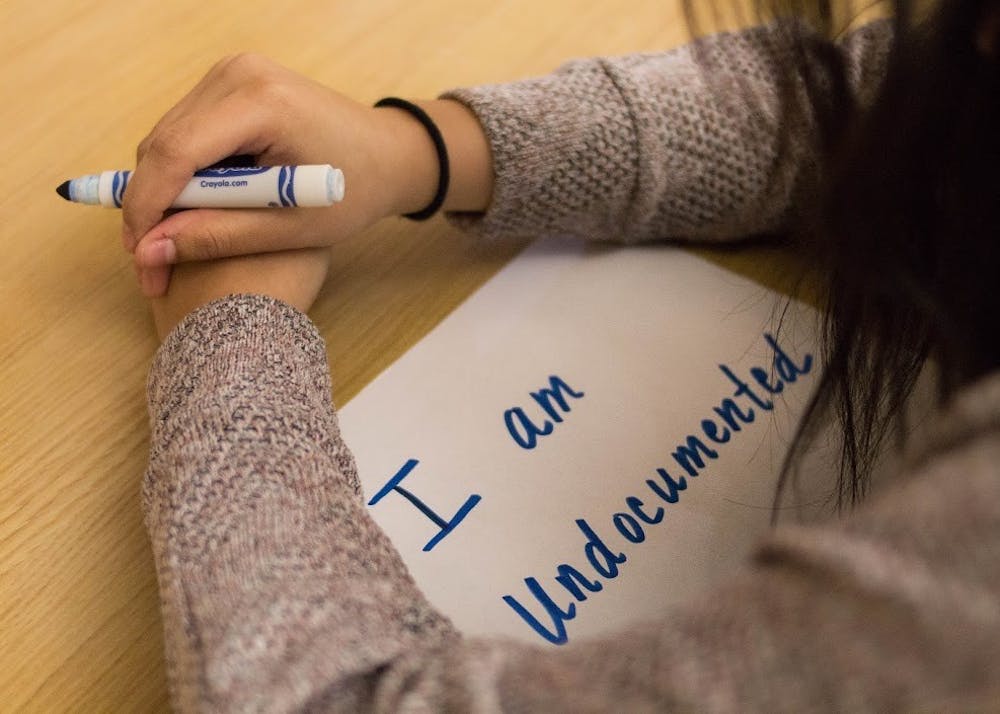

“It is strange to think that I am an ‘illegal person,’” says Ortiz. “Then I think, ‘Does that mean it’s a crime? Am I a criminal?’ I have had thoughts like that before. It’s a weird thought to have — having to connect those two — because you do hear that. ‘They did something illegal — they’re a criminal.’ It’s a strange word to say, ‘illegal’. I think I prefer ‘undocumented’. It is a piece of paper that I’m missing — a green card — that’s all I’m missing.”

Ortiz said that at some point she will try to apply for a work visa, but for now, she is happy with sticking with DACA, which gives her a driver’s license and allows her to work in the U.S.

She’s focusing on how she can be a role model for others in her situation.

Ortiz was back home for fall break visiting her high school when a student who was in the same situation came up to Ortiz crying and said, “I don’t know how you did it, but I want to do it, too.”

Ortiz is comfortable and happy at UP. She’s found friends and a recreational sports team that she loves, and also enjoys drawing and reading.

She doesn’t know what the future will hold, as getting a job in the U.S. without a social security number is difficult, especially in the field she hopes to go into.

But she hopes that one day she’ll be able to travel to Mexico freely and finally meet her grandparents. It’s been 16 years since her parents have seen their families.

“My parents just wanted to come and work and to give me a better life,” Ortiz says. “Sometimes when I say that, I think it’s cliché, but it’s true; they came here to give me a better life — and they did.”