by Cheyenne Schoen |

Tori Dunlap and her boyfriend rode in the backseat of the car, her parents in the front. The four were on a road trip that was going well, until the conversation in the car turned toward that one topic to avoid during family gatherings: Politics.

“Because my boyfriend supports Hillary and my mom does not, things got a bit heated as to their perspective on her and her background,” Dunlap, a senior organizational communications major, said.

The conversation eventually extended beyond the political arena, leading to personal judgements about one another based on their differing views, resulting in a particularly heated fight between Dunlap and her boyfriend.

“It was actually one of (our) worst fights,” Dunlap said. “I was upset with him over fighting with my mom, and that led to all of us being upset with each other.”

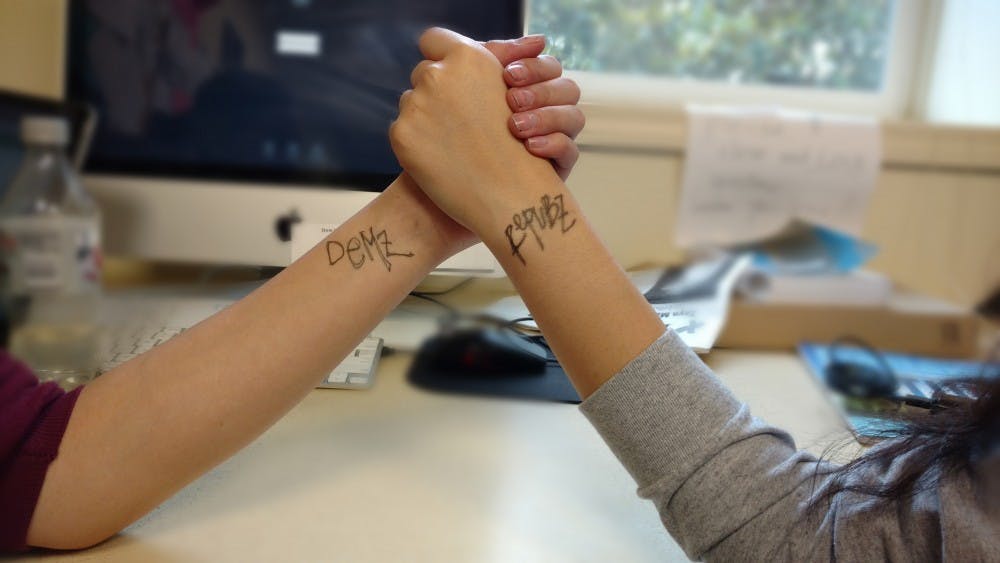

Dunlap’s story of heated political debates is not one unique to her. For most college students, the 2016 race to the presidency is the first and most divisive election they have faced. The candidates have proven everything from entertaining to downright terrifying, which has sparked discussion not only in the classroom, but also at home among students’ families.

For sophomore theology major Niko Strom, the discussion caught fire after he switched his ballot from Independent to Democratic five weeks ago.

“Switching my ballot actually caused a huge problem,” Strom said. “A lot of my family members joked about it, especially when I said I was going to vote for Bernie Sanders. They were so mad. They were like, ‘He’s a socialist, he’s going to ruin America.’”

But Strom says this is the first year he’s felt “savvy enough” to argue his position. When his grandfather brought up the fact that Sanders is a socialist, Strom questioned his grandfather about who the last great socialist president was.

“And (my grandfather) said, ‘I don’t think we’ve ever had one,’ and I was like, ‘FDR. So of the same cloth, you’re saying that FDR was terrible?’”

Strom’s grandfather gave in — just as Strom had suspected.

Provided they vote, millennials could carry a substantial weight in this election. According to the United States Census Bureau, those born between 1982 and 2000 now outnumber baby boomers by nearly 8 million, and represent more than a quarter of the nation’s population.

The 2016 election is also unique because it has seemingly accentuated the generational rift between millennials and their elders.

Political science professor Gary Malecha, who has facilitated many political discussions with students in his classes, theorized that the generational rift may have to do with experiential differences between generations.

“Part of this is, I think, are different experiences,” Malecha said. “For example, there are differences within generations with regards to, for instance, like someone for Bernie Sanders, as opposed to someone in support of Hillary Clinton. I do think we see that borne out in public opinion polls and in exit polls. I think it might be a result of the experiences of different generations. And that may be important in terms of shaping their responses to the candidates.”

The bureau also reported that millennials are more diverse than preceding generations, with “44.2 percent being part of a minority race or ethnic group (that is, a group other than non-Hispanic, single-race white).”

Additionally, 2014 PEW research suggests that the millennial generation tends to tilt democratic, with “51 percent identifying as Democrats or lean Democratic, compared with 35 percent who identify with the GOP or lean Republican.”

But it all depends on whether millennials’ strong political opinions will translate into actual votes.

Junior history major Nicolas Vavuris has felt the divide among his family members as well. He said that political discussions in his house tend to turn into a frenzy of yelling.

“There’s no such thing as a healthy debate,” Vavuris said. “Whoever yells the loudest wins.”

Vavuris said he’s had to keep quiet on issues he and his mother disagree on so as not to become too heated.

“When things that I violently disagree with, like Donald Trump’s thoughts about undocumented immigrants, when those come up I have to fight to hold my tongue because otherwise I want to lash out,” Vavuris said.

Malecha feels it’s important in situations where there are differing opinions to consider both sides of the conversation and to understand that people have valid points for many different arguments.

In a heated situation, Malecha said it is best to take a step back and listen to the other person.

“When talking about politics it can be pretty controversial, but you always recognize you’re talking to your mom, or your dad, and they love you and you love them,” Malecha said. “You have to recognize that, well look, this person that you care very deeply about has these views. And at some point, you have to be willing to respect that and understand why they might be holding this position.”

While the home might not be the most supportive environment to hash out political differences, Dunlap said she has found support for open discussions in her classes.

“It’s finding people who support you, not necessarily who agree with you, but finding people you can have those conversations in a safe and supportive environment,” Dunlap said. “And usually that’s a UP classroom, which is phenomenal.”

Malecha said it’s important not to shy away from having those political discussions, however controversial they may get.

“We need to start entering into conversations that don’t necessarily result in shouting matches and angry discussions, but to try to promote a greater understanding as to why they think this way or that way,” Malecha said.

Cheyenne Schoen is a staff writer for The Beacon. She can be reached at schoen17@up.edu.