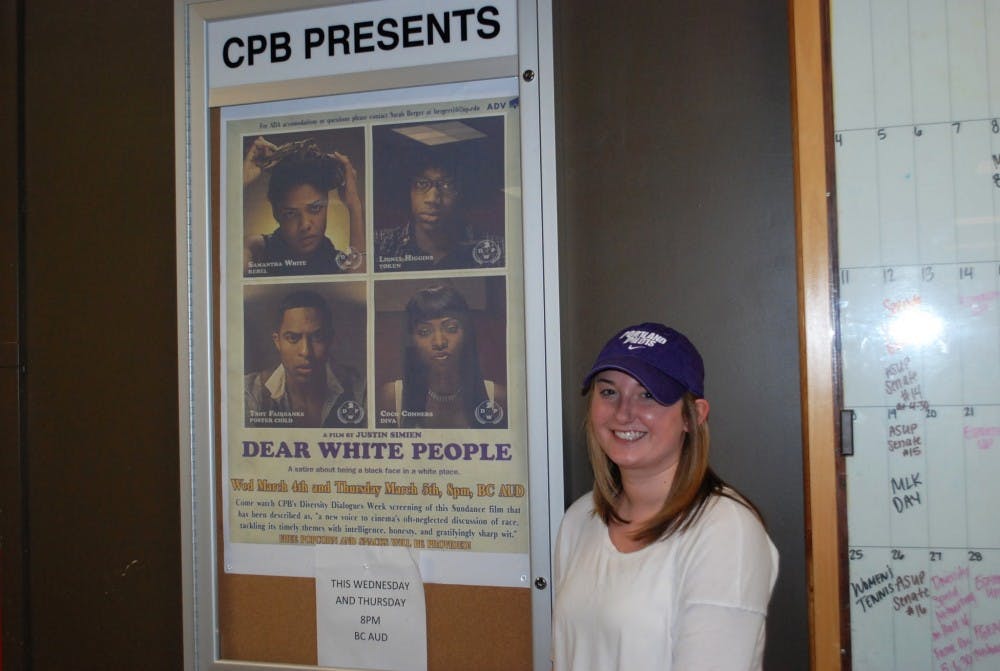

Lydia Laythe |

Tonight, the Campus Programming Board (CPB) is sponsoring a campus-wide screening of “Dear White People,” a film that highlights modern issues around race, as part of Diversity Dialogues Week (DDW). While it’s not unusual for CPB to sponsor film screenings, tonight’s is noteworthy because of the conflict leading up to it.

Diversity coordinators say they contacted CPB for months, starting in November, about participating in DDW.

In an email sent in February responding to the coordinators’ request, CPB Director Sarah Berger wrote, “As of right now, Diversity Dialogues does not fall under CPB’s jurisdiction.”

This part of her email sparked intense concern amongst the Multicultural Programming staff about CPB’s role in addressing diversity and inclusion. These concerns turned into conversations between Multicultural Programming and CPB, but occurred behind the scenes until the issue was raised in an ASUP Senate meeting last month.

Sophomore Joseph Rojo, ASUP Diversity Committee chair, brought the issue to ASUP because a diversity coordinator asked him to see what CPB was planning for DDW. Rojo said CPB members responded quickly with reasons why they don’t address diversity without answering his question.

“I was just wondering what they were trying to do and why they hadn’t responded,” Rojo said. “And all of a sudden I get this reply of: ‘CPB doesn’t deal with diversity because we don’t feel trained and able to do that.’”

Roles and responsibility

Multicultural Programming staff and diversity coordinators were concerned about CPB’s lack of diversity programming given CPB’s financial power. According to the ASUP Budget, CPB was granted $117,800 for the 2014-2015 academic year. This means CPB receives almost 26 percent of the budget, while most clubs and organizations receive less than 1 percent. CPB uses its budget for popular events such as Anchors Away, Dance of the Decades and Rock the Bluff.

Tyler Zimmerman, CPB adviser, said it’s fair to question how CPB addresses diversity and to expect more because it is such a powerful group on campus.

“(CPB is) not just a little club,” Zimmerman said. “It’s reasonable to say ‘How is this incredibly important and influential student organization handling these very important topics? What are big student organizations doing to honor diversity?’”

CPB Director Sarah Berger sees this influence as a tool to bring awareness to diversity and inclusion. But Berger said CPB’s shifting role resulted in some “growing pains” around how to make their commitment to diversity visible.

“We are a changing and evolving organization that has grown immensely,” Berger said. “With that comes a lot of responsibility. CPB is in a really unique place... we have a lot of influence on campus and it’s important to use that influence for good, to bring to light issues that are really important to students.”

But some students, especially diversity coordinators, think a commitment to diversity should always be visible.

Senior Elvia Gaona, a diversity coordinator, said she expected more discussions around diversity given that the organization has over 40 members to work on projects.

“It’s a little frustrating because these people are doing this programming for all students at UP, and a huge portion of that is minority students,” Gaona said. “So the lack of programming there isn’t meeting the needs they’re supposed to be fulfilling for all students.”

For Senior Jordanne Petree, another diversity coordinator, CPB’s initial response was hurtful on a personal level.

“It’s a little bit like saying ‘We don’t care about you,” Petree said. “It feels representative of the University (saying), ‘Eh, we don’t really care about hearing about your queer identity, or your faith identity – even if it’s not intentional.”

An institutional problem

According to Multicultural Programming Director Bethany Sills, this isn’t a new problem.

In 2013, a similar situation arose. Multicultural Programming staff and CPB members, as well as representatives from other campus organizations, held a meeting to discuss CPB’s role in addressing diversity after then-CPB Director Sean Ducey resisted participating in DDW. In an email to diversity coordinators, Ducey said CPB had not set aside money for DDW and he was concerned about attendance.

Eventually Ducey, who declined to comment for this story, decided CPB would participate in DDW. And according to Sills, CPB took great initiative in planning for DDW after the meeting in 2013.

Tynishia Walker, a 2013 alum, was a diversity coordinator in 2013 and participated in those discussions. Walker said she’s not surprised to hear the problems she faced in 2013 are resurfacing.

Walker said student populations change every year in college, meaning change among individuals is possible. But if nothing changes institutionally and culturally, that change won’t last.

“There’s not an institutional legacy left after (students) leave,” Walker said. “I think when I was leaving, I saw the University as a whole moving backward (in regards to) diversity… No one was left to continue that conversation.”

According to Sills, the major institutional or cultural problem is a “compartmentalizing” of diversity programming, in which only a select few are deemed qualified to address diversity.

Tyler Zimmerman, CPB adviser, echoed this concern.

“I think there’s a temptation to view diversity work as a responsibility of a select few that elect to do it,” he said. “I think that if you default to ‘I’m not an expert in diversity topics,’ you’re doing yourself a disservice.”

But according to Sills, every student is qualified to address diversity.

“When we talk about diversity, it’s an evolving conversation about identity,” Sills said. “Anyone can experience the grand mosaic of identity in some way, shape, or form.”

According to Sills, this “compartmentalization” may be inhibiting CPB’s scope from accommodating diversity programming, but this initial conflict could be a turning point.

Moving forward

CPB leadership is, in fact, asking questions about CPB’s role in addressing diversity. Berger and Zimmerman discussed diversity training during CPB retreats and meetings or having a CPB liaison to diversity coordinators as ways to ensure diversity and inclusion are more clearly woven into the structure of CPB.

“If we can encourage an environment that fosters community while taking into consideration diversity concerns, we want to do that,” Berger said. “We want to make sure we make (diversity and inclusion) part of the CPB culture, so that it’s just an expectation.”

But Berger knows it won’t be simple.

“We definitely realize that this issue is not going to be solved by one conversation, or two movie screenings,” Berger said. “I think (our goal now) is finding ways to make it known that diversity is important to (CPB), not just during Diversity Dialogues Week, but throughout the year.”

Sills understands the complexities of diversity and knows it requires time, but she hopes these discussions will create change to prevent similar issues from happening again.

“We’ll never be perfect,” Sills said. “But we can always improve.”

Lydia Laythe is the opinions editor for The Beacon. She can be reached at laythe16@up.edu.