By Malika Andrews|

They threatened to kill him if he showed up at the game.

His coach warned him not to go.

But Korey Thieleke did show up, ready to play basketball.

His dad carried a pistol. Just in case.

Although Korey was not involved in gangs, his father’s reputation as a gangster clung to him.

Marching shoulder-to-shoulder between his dad and a friend, Korey made his way to the locker room with a chorus of boos and threats following him.

As he set foot onto the court, he felt his phone vibrate and reached into his pocket to see a text from his mother: Is homeboy that threatened you wearing a navy blue Yankee hat?

Korey glanced up to the bleachers, his eyes met his mother’s and he nodded.

Korey’s mother, accompanied by members of the Bloods, sat down behind the Yankee hat.

Yet there was no time for Korey to focus on the threats, no time to focus on the boy in the Yankee hat. It was game time.

The hostility followed him out to the high school parking lot after the game.Threats of kicking in his grandmother’s teeth echoed in his ears as his father pushed him into the backseat of the car and drew his gun.

No shots were fired. But Korey knew he was hated in basketball because of where he came from.

It didn’t matter - sports would be his way out.

Something else about that night: Korey hit the game-winning shot. At the buzzer.

Now, Korey tells this story casually. As if it were no big deal.

Five years later, after coming to The Bluff without so much as a pillow, Korey has shown he can not only survive outside of Bakersfield, California, he can thrive. He has become a successful student, a two-sport athlete and a mentor for high school students.

But going from gunfire in Bakersfield to graduation on The Bluff wasn’t without struggle, one that makes success even sweeter than the sugar sandwiches he ate in his youth.

https://youtu.be/61TozrOJY-Y

VIDEO by Hannah Baade

Bakersfield boy on The Bluff Under layers of smog and between gunshots fired, lies Bakersfield, 143.6 square miles of hell.

“Growing up in Bakersfield was pretty rough,” Korey said.

Through 16 social workers and 18 years of foster care, Korey battled the odds.

There were times he didn’t have a bed to sleep in. Nights he curled up on the cold cement floors of garages all over the city.

His own great-grandmother, who was white, forced him to sleep in the backyard when he visited because of the color of his skin.

Money was tight. With an allowance of only $5 a month, Korey learned to steal to survive. His grandparents used foster checks to pay the bills.

Still, Korey battled on.

His determination was recognized by men’s basketball coach Eric Reveno on a recruiting visit to West High School Korey’s senior year.

Reveno wiped away tears when he thought about the path that led Korey to the University of Portland.

He remembers sitting with the guidance counselor at West High and discovering Korey had unimpressive grades, but a determined spirit.

The counselor, Reveno remembers, insisted Korey deserved a chance. She looked at Reveno and said, “It’ll be interesting to see what the Bakersfield boy does out of Bakersfield.”

“I’ll never forget (that),” Reveno said. “And I didn’t really know what that meant in terms of what a Bakersfield boy was. But now I know. She meant, with the neighborhood he was from, and that environment, she had seen lots of kids like him that hadn’t gotten out of Bakersfield, that hadn’t gotten the opportunity.”

Reveno saw a kid that deserved a chance.

Korey ran with that chance and became not only the first member of his family to graduate from high school, but the first to attend college.

The first to free himself from the restraints of Bakersfield.

The battleground moved from the streets of Bakersfield to Portland’s bluff.

When Korey arrived, he brought only what he could afford with $125 savings: house slippers, two pairs of Converse sneakers, a pair of jeans, sweatshirts and a few T-shirts. “People called me homeless,” Korey recalled.

Just weeks after coming to The Bluff, a staph infection from an infected tattoo put Korey in the hospital for a week and kept him out of the gym for months.

In contrast to his buzzer-beating game winners of high school, Korey came off the bench for the Pilots.

His sophomore year, the Pilots won only three conference games. Korey understood why he couldn’t play as a freshman, but as a sophomore his patience was wearing thin.

He remembers thinking, “Well damn, we ain’t winnin’, why can’t I play?”

Coaches at UP even encouraged Korey to transfer schools because he would not get the playing time they thought he deserved.

Frustrated and angry, Korey nearly gave up. But advice from his high school coaches brought him back to reality.

He remembers the phone call well.

“They told me ‘Whatever you go through up there, can never be as hard as what you go through down here,’” Korey said.

And it was true, he had survived worse. Korey realized that even if UP coaches thought he would be better off somewhere else, he needed to stay and play.

This was the game versus Richmond all over again - his coaches told him no, and Korey showed up to play anyway.

This time, the Chiles Center was the battlefield.

Korey knew, if he left, there would be nowhere to go. Going back to Bakersfield would hand him a one-way ticket to jail, or worse.

He had finally found a place he felt he belonged.

“My boys is here, they’re my family,” Korey said. “I ain’t just gonna leave. There is no point.”

So he fought. He built up his strength and weight. And then he played.

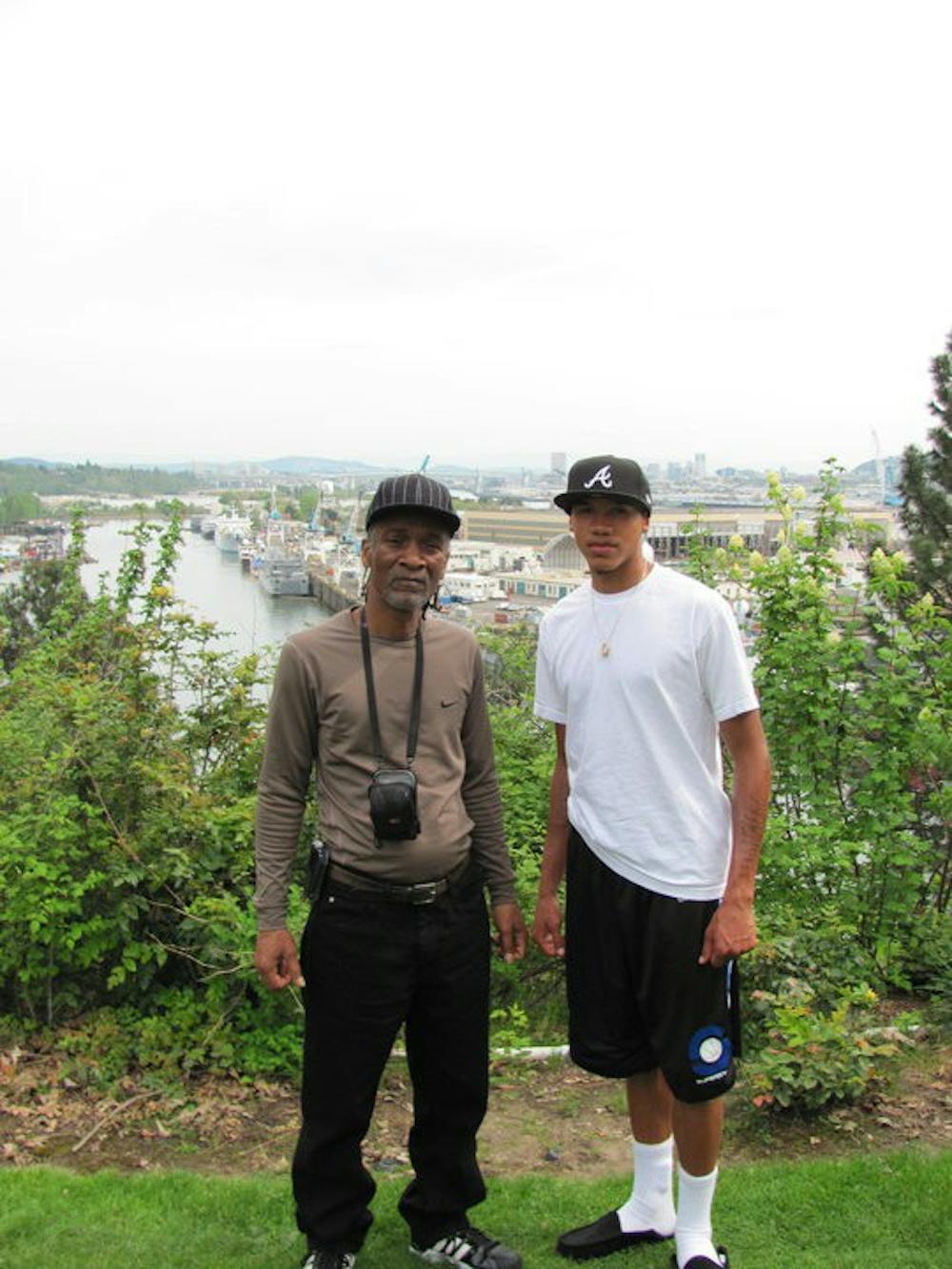

Junior and senior years were full of flashy dunks, and big wins against BYU and Gonzaga. On senior night, his worlds collided as he stood beside his father and accepted flowers and praise from Reveno.

It was the first time he had spoken to his dad in months, and the first time he had seen him in years.

“My original plan was to have my grandparents come up,” Korey said. “But they couldn’t afford it. I was gonna be the only person with no one up there, so coaches recommended my daddy come.”

Still, Korey smiled, and his father was there to see the life his son chose instead of gangs.

“When we recruited him, we saw he was a kid with the potential to be special,” Reveno said. “Boy, were we right.”

A Second chance When basketball season was over, Korey found himself at a familiar crossroads. He felt the same way he had four years ago.

He did not know what to do.

Going back to Bakersfield was not an option. Scared and lost, he waited for graduation to come, making no plans, but knowing Bakersfield was a graveyard for his dreams.

Weeks before his college graduation, head cross country coach Rob Conner approached Korey with a proposal to stay a fifth year and run for UP.

Korey had been a track star in high school, graduating as one of the top six sprinters in California.

With a fifth year at UP, in a shiny new pair of cleats, a long way from ratty tennis shoes and the dusty track of West High, things started to come together.

‘What’s the latest and the greatest?’ Few of Korey’s teeth are real.

His top two teeth cracked when he was pushed into a basketball pole during a pickup game in middle school. His bottom teeth were ripped out of place when he was jumped for crossing the imaginary line that divides gang territories.

Still, Korey sports his infectious grin as he approaches friends, asking the same question he picked up from E-40’s rap lyric:

“What’s the latest and the greatest?”

Every time, this same phrase. An attitude of just-find-some-way-to-be-happy that has has helped him survive.

When Bakersfield beat him down, basketball and his grandparents held up the corners of his smile.

“[Basketball] kept me busy,” Korey said. “Even though I was not liked in basketball, it still kept me out of jail and all the gang trouble that people was getting into.”

When his mother’s drug addiction prevented her from being able to care for her children, Korey’s grandparents took him and two of his siblings in.

His grandfather, Johnny Hobson, made sure Korey walked the line, making sure he stayed out of the gang life he lost his son, Korey’s father, to.

He told him repeatedly that making millions was not the goal, but an education was necessary. College was necessary. And basketball was his ticket to that education.

“I used to get on him about doubting himself,” Hobson said. “You can do a lot of things other kids can’t do. You are blessed. Look what gangs got your daddy into. Look what drugs got your mother into. School isn’t for play, go and learn. Just needed one (grandchild) that wanted to do it straight. It was amazing, he was the one to do it.”

Korey’s grandpa fought the battle for him when he didn’t believe he was strong enough to fight it himself.

In a city that knows no love, Hobson believes that is the ingredient that most kids are missing.

“These kids were just lookin’ for someone to love,” Hobson said.

No fear of the streets There are few people Korey allows to see into his past. He doesn’t want it to define him. In four years Korey has set foot in his grandparents home in Bakersfield three times. He came back to UP early his sophomore year after he saw a man killed, was shot at and narrowly escaped being jumped.

Makayla Lindburg, Korey’s girlfriend and a UP volleyball player, has been to Bakersfield and sat in the sweltering heat of the grandparents’ living room.

She describes Bakersfield as the opposite of her small hometown of Prineville, Oregon. The city is anything but welcoming. People are cautious and untrusting of the world outside their screen doors.

But Korey, she says, is strong.

“He has no fear of the streets. He doesn’t fear the things that most people are afraid of,” Lindburg said. “I’ve never met someone like him that can endure so much and be both outgoing and so humble and caring at the same time.”

Parkrose: A different West High Cali Bred. These words are tattooed in bold on Korey’s right and left forearms. Family is tattooed on the back side of his right arm. They are tattooed badges of honor.

Korey is not ashamed of where he came from. He’s grateful for his grandparents, how they did the best they could with what they had.

In addition to track and a full class load, Korey got a job working 13 hours a week as an AVID tutor for Parkrose High School, a public school in Northeast Portland.

The Advancement Via Individual Determination (AVID) program, aims to “close the gap between the educational performances of student groups, especially groups defined by economic status, ethnicity and gender.”

Korey helps kids who are earning low grades but want to go to college.

“Parkrose is just a different West High,” Korey said. “The kids is just like West, they don’t want to listen to nobody. If they don’t go to school, they gonna end up on the streets.”

68 percent of the students at Parkrose are economically disadvantaged. Korey went through a similar program when he was in high school to help maintain grades eligible for college.

Recently, Korey became an assistant coach for Parkrose’s track team.

“I can relate to them more than anybody I work with,” Korey said. “Because even when they give me crap I’m like, ‘Dude, come on now, everything you do is a rerun. I done seen it all, I done it all.’”

With only two months left at UP, time is squeezing Korey to make decisions about his future. There are whispers of Olympic track training, but for now he has his eyes set on continuing his work with AVID and helping kids to fight the battle he feels he has won.

Today, Korey is 864.5 miles from the city that could have destroyed him. Any tribulation he faces now, cannot compare to where he came from and what he survived.

“Yes, we ate sugar sandwiches and didn’t have no clothes, got my teeth knocked out, got shot at…but I’m here. I’m still standing.”

Malika Andrews is the Sports Editor for The Beacon. She can be reached at andrewsm17@up.edu or on Twitter @malika_andrews.