What do UP professors make?

There are generally three levels of rank for university professors: full professors (often referred to simply as “professors”) have tenure and the highest academic rank; associates are mid-level, usually tenured professors; and assistants are entry-level, tenure-track positions.

According to 2015-16 data from the Chronicle of Higher Education, the average salary at UP was $85,176 for full professors, $75,465 for associates and $65,844 for assistants. These are averages for all professors and within these categories, salaries may range; for example, assistant engineering professors would be on the high end and assistant communication studies professors would be on the low end of the salary scale.

On average, full professors at four year private colleges made $122,422 in 2015, associate professors made $81,698 and assistants made $67,611, according to that same data set.

Salaries at UP came somewhat closer to the averages of other Master’s universities, for which 2015 average salaries were $93,331 for full professors, $75,195 for associate professors and $63,671 for assistant professors.

A group of professors involved with the Academic Senate’s Faculty Welfare Committee (FWC) conducted research over three years, comparing UP professors’ salaries with those at other schools.

But Greene said the consultant hired to analyze faculty salaries at UP has worked with a number of universities in the past and will have access to more data than was available to UP professors.

One of the professors who worked on the study is Bill Barnes, an associate professor of economics and environmental studies, who said he spent hundreds of hours over the past three years collecting and analyzing research related to faculty compensation.

“The goal in all of this is to have a situation where faculty feel fairly compensated and respected, and the institution benefits because faculty are empowered, happy and productive,” Barnes told The Beacon. “We don’t want faculty to get distracted or unproductive through lower morale or pursuing alternative employment to make ends meet.”

While many professors are optimistic that the consultant will be helpful, some say that the response from administration overlooked the hard work that the FWC and other professors invested.

“I think one of the biggest source of concerns with the response that came down is that it did not respond to the enormous amount of work that people in the FWC, including some of our economists in the business school, actually did,” said Jeff Gauthier, a full professor of philosophy who has taught at UP for 25 years and will be getting a raise. “This is years of hard work, and I think a lot of the faculty felt that that was basically ignored.”

Academic Senate unanimously passes salary resolution

Professors at all levels were frustrated with the terms of administration’s decision. On March 23, the Academic Senate voted unanimously to pass a resolution in response to the February raise decision. The Senate is a forum for professors to make recommendations to administration, but does not actually dictate policy.

In the resolution, faculty ask for a $5,000 corrective raise for all professors spread over the 2017-18 and 2018-19 years, regardless of rank.

According to Barnes, the request is intended not only to bring UP's faculty salaries more in line with those at similar institutions, but also to reward faculty for experience and merit.

The resolution itself says many faculty members are concerned that the administration's decision to award corrective raises to only some professors "will erode morale when it is already dangerously low."

Faculty point out that under the administration's plan, new assistant professors in their first year at UP will now make $60,000, while professors who have taught for years at UP could be making just $61,000.

Michael Connolly, a full professor of performing and fine arts, stood up at the Senate meeting and read a statement in support of the resolution.

“I support this resolution because it pains me every year to learn that UP has been named as a best buy in higher education on the West Coast by Kiplinger magazine,” Connolly’s statement read. “I cringe because I know this award is earned on the backs of many of the faculty and their families.”

Who are UP’s peer institutions?

Last April, Greene and Timmins proposed a “peer group” of comparison schools to the FWC, which included 13 colleges in Washington and Oregon, and the FWC analyzed those schools’ salaries compared to UP.

The FWC also compared UP to the peer group used by UP’s Office of Institutional Research, which includes 11 schools from Washington, Oregon, California, Texas, Minnesota and Massachusetts. UP uses this peer group and three other groups to compare tuition, endowment, financial aid and enrollment.

The reason the same list of peer schools is not used to compare faculty salaries, Greene and Timmins say, is because tuition setting is based on regional comparisons, but when setting compensation, it’s more important to compare programs.

“When it comes to compensation, certainly regional concerns are also a variable, but more importantly, comparing programs becomes important,” Greene said in an email. “For example, an engineering program is more expensive in actual program costs (materials, facilities, equipment) and compensation than say a theology program. Not all those schools have engineering, nursing programs, etc.”

In both comparisons, the FWC found that salaries for faculty and staff are relatively low, as a percentage of spending, compared to these peer groups.

In October 2016, Greene and Timmins again gave the FWC a list of comparison schools to use as a benchmark—this time, a list of about 100 universities around the nation. The FWC analyzed data from those schools using information from the 2015-16 AAUP Faculty Salary Report and controlled for the cost of living for each school’s region.

The FWC detailed its findings in a 41-page report, revealing that 93 percent of the listed schools have higher full professor salaries than UP, 73 percent have higher associate professor salaries, and 72 percent have higher assistant professor salaries when salaries are adjusted for the cost of living.

The FWC findings also show that Portland’s cost of living is significantly higher compared to the average of the other 100 schools.

But Greene and Timmins say the FWC data isn’t comprehensive.

“The problem comes down to: What is the comparison group? What are we going to benchmark ourselves against?” Greene said. “We never really could find the comparison group we all agreed on… Casagrande will help us access deeper data than professors in the business school can.”

The cost of living in Portland

As in past years, all professors will also be eligible for a percent merit pool raise — this year, it will be 2.5 percent of their current salary. But that doesn’t necessarily account for the rising cost of living in Portland. At best, it helps to keep up with the local inflation rate, which is up 2.6 percent from a year ago, according to the U.S. Labor Department.

The cost of living in Portland has gone up considerably in the last 10 years and home prices increase each month. An April 2017 RMLS Action Report says the average home price in the Portland Metro area in Feb. 2017 was $404,200, a 10.8 percent increase over Feb. 2016’s average sale price of $364,900.

And according to MIT’s living wage calculator, a family with two adults and two children must make $72,164 before taxes in order to live with the most basic needs in Multnomah County.

Many professors cannot afford to live in the Portland metro area with their families and instead commute to school from places like Vancouver and Gresham, where the cost of living is more affordable.

“We’re not asking to be rich, but we’re asking to be able to live in a comfortable, middle-class lifestyle in Portland,” said Gauthier. “It’s just difficult when you’re trying to raise a family and you’re trying to get by and your salary is not keeping up with the cost of living.”

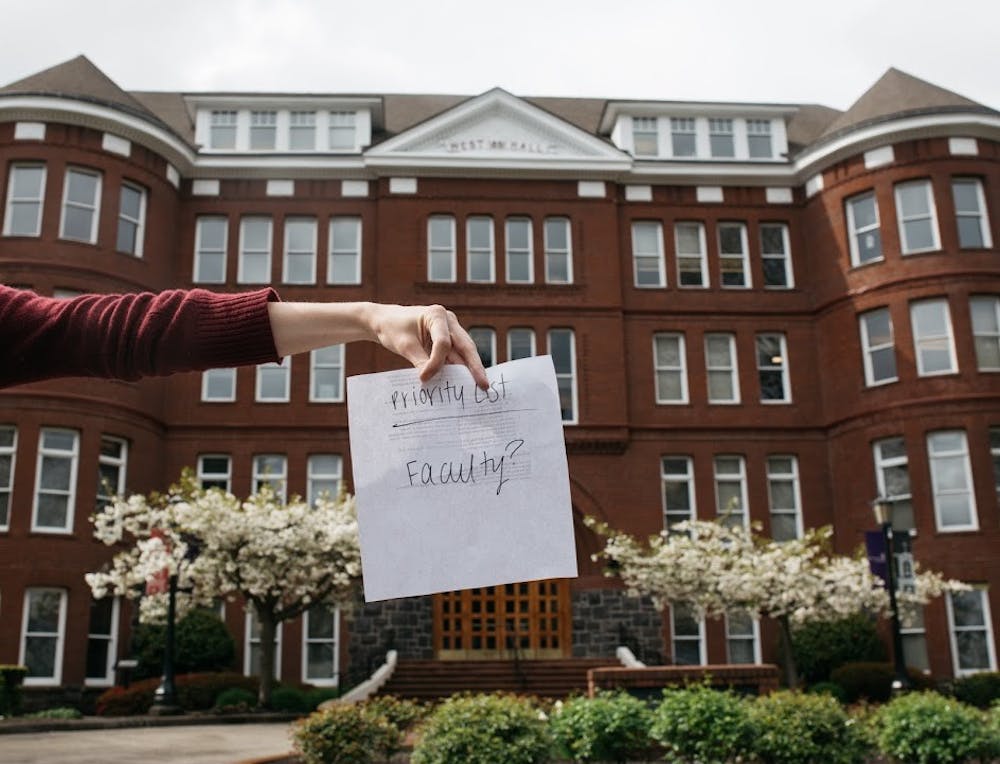

Faculty questions administration’s priorities

While the money is one issue, professors feel like the underlying problems are priorities, respect and community.

“What faculty are asking for is for there to be a shift in those priorities and for faculty to be thought of a lot more highly on that list,” Alejandro Santana, an associate professor of philosophy who will not be getting a raise, told The Beacon. “We are in this because we care about higher education, we care about students, we care about the mission of the University, and when we see this problem continue, I start to wonder, ‘Well, maybe we’re not the community I thought we were.’”

Norah Martin, a full professor of philosophy and environmental studies who has taught at UP since 1994, echoed Santana’s statement, saying she feels faculty are not the University’s priority.

“What the faculty do is taken for granted and, in some ways, what the faculty do is not being valued,” said Martin. “I’ve committed many years of my life to this institution and I really care about it. When I see things happening that are damaging to the institution, I want to do something about it, and I think this is damaging to the integrity of the institution when the faculty feel so disrespected.”

Echenique said it’s important that the Catholic values and mission of the university be in line with both the administration’s response and the professors’ approach to the issue.

“We have to consider fairness and social justice at the center because that’s what we want to radiate outside of the University,” Echenique said. “The way we address and solve this really tells who we are as an institution.”

But Greene says he thinks the FWC doesn’t necessarily represent all the professors at UP.

“I find (the low morale) discouraging, but I’ve had a lot of professors come to me and say they didn’t think the FWC represents them, too,” said Greene.

While the future of wages for the faculty is uncertain, for now, Greene, Timmins and the FWC have agreed to work together with the consultant in hopes of finding a solution all are content with.

“We can’t guarantee that every compensation problem is going to be solved next year; there are a lot of variables,” said Greene. “As we have some data for next year, we are going to try to act. It’s not going to be two to three years before they see a change, but we want it to be a fair, sustainable, repeatable compensation process.”

Says Professor Norah Martin: “We need to see what happens. I think communication needs to be improved, and in particular, communication about the financial situation of this University.”

--

Clare Duffy contributed to this story.

--

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that the FWC voted unanimously to pass the resolution on raising faculty pay. It was, in fact, the Academic Senate.

Clarification: An earlier version of this story reported the consulting phase could take up to three years. More precisely, implementation of the consultant’s recommendations “will occur in the subsequent 2-3 years in accordance with Vision 2020 (strategic plan),” according to a Feb. 23, 2017 memorandum to faculty from Tom Greene and Alan Timmins.

Clarification: A subheadline in an earlier version of this story used the term "across-the-board pay increases" to describe the request in the resolution passed by the Academic Senate. While it is true the Faculty Welfare Committee has asked the University to raise compensation for all professors, the focus of the resolution is on professors not already awarded corrective raises.