Students dig up America's racist past

UP students get involved in creating a national memorial to victims of lynching in the Deep South

The summer heat was already fast approaching though it was only May. Thirteen students knelt in the shade of the tall oaks in the woods of Eastern Alabama. Each person was on all fours, both knees and one hand in the dirt and the other hand gripping a trowel.

For those students in that moment, the trees were protection — protection from the sun, from the blistering heat.

But more than 100 years ago, in 1877, those trees were not shelter, but witnesses to the killings of seven black men.

The men were drinking from a well, when the white well owner found them and threatened them, even reportedly shooting at one man as he tried to drink. Later that night, a mob of white men returned and killed all seven men, leaving their bodies in an attempt to intimidate other members of their community.

The standard definition of lynching is an intentional killing, often by hanging, that is not necessarily racially fueled. However, lynching is deeply connected to violence against black communities in the South and throughout the U.S. for hundreds of years.

Flash forward to May 2016: History was dug up as these University of Portland students collected soil from that lynching site as a part of a national memorial.

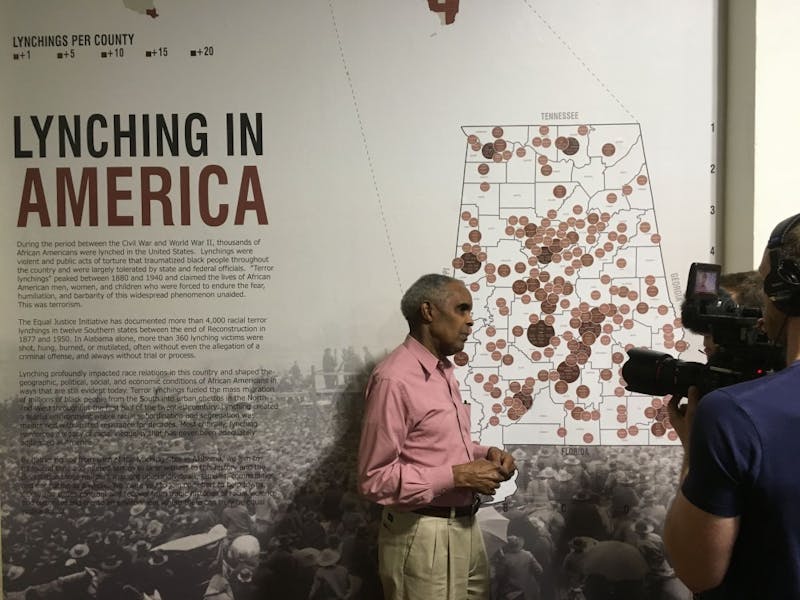

The project is sponsored by the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Ala., which provides legal representation to inmates on death row. The founder of EJI, attorney Bryan Stevenson, who was recently profiled in the New Yorker , told the students and dozens of other volunteers that their efforts would help create a national lynching memorial in Montgomery, a city where hundreds of slaves were put up for sale every day in the decades leading up to 1865, when Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment, making slavery illegal. But even after that, racial oppression continued in new ways including lynching of black Americans.